|

Chief Bill Lellis (ret) is LIVE! today with the second Code Three LIVE! blog at 2:00 pm PDT. You can click HERE to watch at 2 or use the convenient button on the home page.

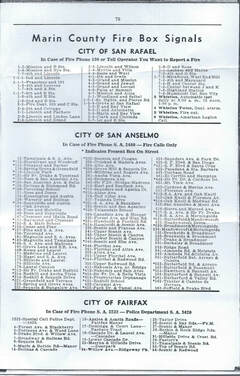

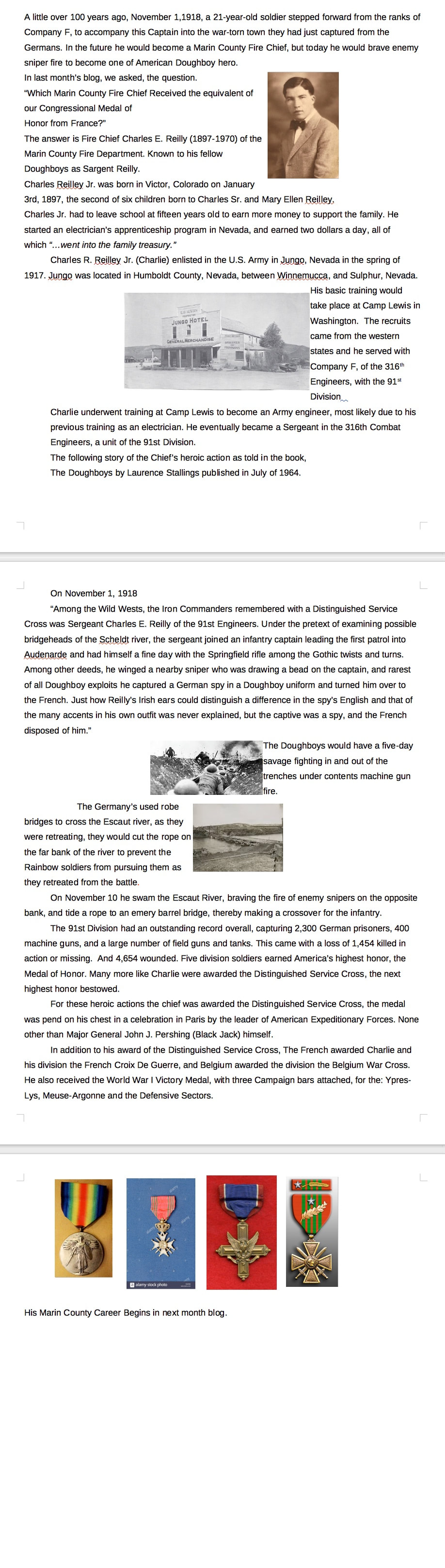

Today Bill does an overview of Marin County (because he thinks at least 3 people in the world may not know where it is), he looks briefly at the 1906 earthquake during this anniversary month. And we remember Tom Forster who founded this web site. Next month on LIVE! Bill will have a surprise LIVE! guest and he will take your questions and comments LIVE! also. The monthly format is: Week 1 - a written blog Week 2 - a new Video of the Month Week 3 - written blog on a different topic Last week - The Code Three LIVE! Send us your comments and suggestions for future blogs and programs. We are looking for ideas of interest to our audience. Email MARINFIREHISTORY@GMAIL.COM SEE you today at 2 pm LIVE! right here. SOUNDING THE ALARMby Chief Bill Lellis (ret)  The following tale tells the story of how the early volunteers’ firemen were alerted to a fire in their community. One must imagine that this was repeated throughout the county. Since this country was founded, notifying the community that a fire was threatening their town was a very challenging task. In order to prevent the colony of New Amsterdam, from burning down in 1648 Governor Peter Stuyvesant, hired six men to patrol the town at night, looking for the possibility of a fire. The instrument they carried to notify the citizens of a fire was called the “rattlewatch.” Once a fire was discovered, they would sound their rattlewatch, and the citizens were required to respond by law. At nighttime, each home had to leave three full buckets of water outside their front door, which the men responding to the fire would grab and apply on the fire.  As communities grew and fires became more frequent, the best way to call the citizens to fight the blaze was to sound a bell on the village’s tallest building. In Larkspur, they built a 50-foot tower next to the Catholic Church on the corner of Cane Street and Rice Lane. It was the volunteer’s responsibility to maintain the bell, rope and the tower itself. Even in 1909, kids would be kids. So, the town trustees had to invoke an ordinance that the bell could only be rung for church services and in the event of a fire. Our Country’s most famous fire bell is the Liberty Bell. The first telegraph fire alarm system was developed by William Francis Channing and Moses G. Farmer in Boston, Massachusetts in 1852. Two years later they applied for a patent for their "Electromagnetic Fire Alarm Telegraph for Cities." In 1855, John Gamewell of South Carolina purchased regional rights to market the fire alarm telegraph, Later obtaining the patents and full rights to the system in 1859. John F. Kennard bought the patents from the government after they were seized after the Civil War, and returned them to Gamewell. They formed a partnership, Kennard, and Co., in 1867 to manufacture the alarm systems. The Gamewell Fire Alarm Telegraph Co. was later established in 1879. Gamewell systems were installed in 250 cities by 1886 and 500 cities by 1890. In 1910, the volunteers began to install fire alarm boxes throughout the town. In 1910, the first one was placed at the intersection of Magnolia Avenue and Ward Street and the bell was mounted on the outside of the firehouse. Once they had money from the dance, they decided to install the state of the art Gamewell Fire Alarm System. In 1925, at the cost of four thousand dollars, they hired two volunteers who were electricians by trade to install 33 alarm boxes through old town. The key to reporting an alarm . When the first street boxes were placed in service in the 1880’s the key to open the box and pull the lever down was not attached to the box. Rather there would be a sign on the box telling the reporting party the key was in one of the stores near by. So they would have to run to the store hoping the place was open, get the key, run back to the box and report the fire. It was quickly realized in the large cities in America this was not a good idea. So they began to attach the key to the box, but kids would break them off putting the box out of service. Along came the Dog House, that little building attached to the alarm box door, protecting the key. But you still had to find a sharp object to break the glass to open the box. The citizens now had a fire alarm  box within running distance of their homes. The chief of San Rafael stated, “It was the finest alarm system in the county.” The red fire alarm boxes were placed on utility poles or on buildings. The system was a low dc voltage running on 0.100 milliamps (MA) power. The boxes were on a closed loop system. Every box had its own coded wheel and every time the wheel came in contact with the circuitry it opened the system, and the air horn on top of city hall would blast. In the station, there was a Gamewell receiver that would interpret the firebox code. The system had a punch out reel on a counter, and every time the horn blew it would punch out a hole in the paper tape. The entire cycle of the box being received at the station lasted as short as a minute. The first volunteers who arrived at the station would read the tape and mark a blackboard telling all other responding volunteers the location of the fire. Regulations entered the alarm system when Underwriters required that the original circular hole be replaced with a triangular indicator on the tape. The reason being Underwriter’s wanted to make sure the fireman rolled the tape in the proper direction so the tape could be reviewed for insurance purposes.  The diaphone was a noise-making device best known for its use as a foghorn. The Gamewell Corporation, of Newton, Massachusetts designed a smaller version for use on fire stations throughout the country. After city hall was constructed in 1913, the volunteer’s would take advantage of the 70-foot towers at the rear of the building. On the top of this tower, they placed a Gamewell diaphone air horn. At the bottom of the tower was an air compressor that would provide the 75 cubic feet of air a minute, at a pressure of between 35-40 psi. The pitch of the Larkspur horn generated 210 Hz. and could be heard throughout the town, it had a range of six miles, on a quiet day. It was tied into a special Gamewell clock at the fire station. The horn blew at 8am, 12:00 noon and at 5 pm. This was to test the air system and the electrical circuits to see that they were in working order. When the 5 o’clock horn blew, the children of the town knew it was time to stop playing and to come home for supper. The alarm system was retired from service due to the cost of maintenance and that more modern notification systems were entering the fire service. The alarm system is currently on display in the Historical Room at the Main Station at 420 Magnolia Ave. The town of Ross fire station still has a wonderful alarm system on display,,  What does the Plectron Corporation in Overton, Nebraska have to do with telling the volunteers they have an emergency call and their help was needed? A plectron was a specialized VHF/UHF single-channel emergency alerting radio receiver. The department began purchasing these home receivers in the 1960’s, to be put in each volunteer’s home. They were activated by a tuning fork rated at 3000 Hz (Hertz). The fork was hit against a solid material while the radio channel was being held open. The Plectron receivers had a device that vibrated at its prescribed frequency and closed a relay. Initially, these modules were reeds that vibrated. Once the relay closed, it latched, requiring to re-set, as the reed only vibrated for a short time. For all intended purposes it was the first piece of equipment that brought the department into the electronic age. If a volunteer wanted to monitor the counties radio traffic, all they had to do was to turn it on. In those days a majority of departments were on the radio frequency of 46.50 MHz If they were not home at the time of the alert, a light on the unit was on telling them they had a call. Like all systems, they were replaced with a new generation of electrical notification devices. The home receivers were replaced with new pagers that the volunteers wore on their belts, so both the street boxes and the plectron went into retirement. On the 4th of October 1931 a street wise cop made is comic depute, His name would be Dick Tracy. And in 1946 cop would bring to the world the first twoway radio watch, and 60 years later the fire service will have at their desposal a new way of communication to the fire service when Appril came out with it’s digital two way wrist watch.  In the last years of the Larkspur Association of Volunteer Firemen, the digital age came swooping out of Silicon Valley, and the ability to transmit a fire alarm to the volunteers would come bouncing off cell towers. The age of Dick Tracy “I Watch” has arrived. |

AuthorOur Blog announces new site content, and gives the context of the topic and it's relationship to fire service history. Written by Bill Lellis & Paul Smith Archives

August 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed