Introduction from Tom Forster, Marin Fire History:

So where the heck is Tocaloma? Historian and Author Dewey Livingston has been a good friend to the Marin County Fire History project, and has graciously agreed to share an excerpt about Tocaloma from his upcoming book. We asked him for this since we are guessing most readers will be unaware this place even existed. Thanks Dewey! The link to our project is not only with several historical fires in that immediate area, but also the fact that Tocaloma was the birthplace in 1887 of Marin County Fire Department Chief Sam Mazza, who tragically died in the Line of Duty at a fire in Nicasio in 1948. His story can be found under our Line of Duty Deaths menu.

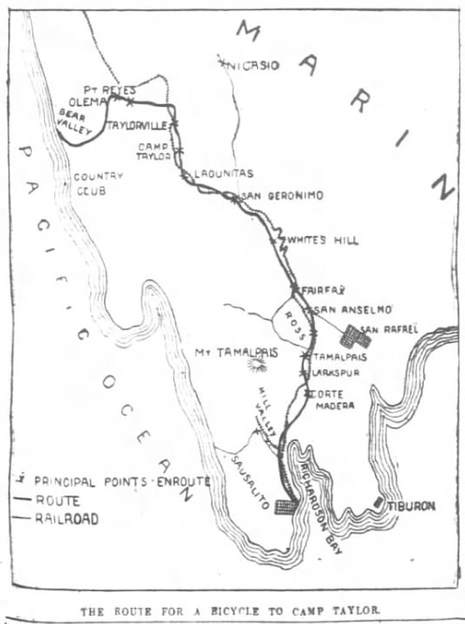

It is important to view historical fires in the context of the time and place in which they happened. 1916 was two years after World War I started, although America would not enter the conflict until the following year. Marin County had a population of only about 10% of what it is today, or 26,000 people spread over the vast area. Very few of the roads were paved back then, but were was railroad service linking most populated areas, including right next to where this fire was. The Northwestern Pacific Railroad line ran up the Ross Valley, came through the Bothin Tunnel linking Fairfax and Woodacre, continued out to Point Reyes Station, and went on up to Cazadero in Sonoma County. The Golden Gate Bridge would not exist for another 21 years, and the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge was not in service for another 40 years. The Mt. Tamalpais and Muir Woods Railroad was very much in business, including the Tavern of Tamalpais, which would burn down in 1923. Read about that under our Major Fires, Incidents menu>Structure Fires, 1923.

While the short-lived Tamalpais Fire Association had formed a few years prior, the Tamalpais Forest Fire District would not be organized until the following year. The Marin County Fire Department did not exist until 1941, after the TFFD ended. The fire departments operating at that time included Sausalito, Mill Valley, Corte Madera, Larkspur, Ross, San Anselmo, Fairfax, San Rafael, San Quentin, and Novato. Almost all of the firemen were volunteers, usually working and living in the towns where they served. Motorized apparatus was in its infancy, with the first motor-driven chemical engine known to be purchased coming to Ross in 1910. Fire hose carts and wagons were still in use, and water systems were limited. Firefighting at that time still included community members willingly jumping in to help save furniture and belongings from burning structures, with most buildings usually burning to the ground within a few hours.

The name Tocaloma is believed to be of Miwok Indian origin, with the ending suggesting -yome, meaning "place", where an Indian village may have been located. The nearby stream was once called Arroyo Tokelalume, and the Central Sierra Miwok language included tokoloma, meaning "land salamander." Did you know that Tocaloma is just 1/2 mile west down the dirt road, creek, and rail line from the Pioneer Paper Mill that Samuel P. Taylor built in 1856? It was a huge structure, and the very first paper mill on the entire West Coast of America, supplying paper to businesses such as all of the major newspapers of the day. Sadly, it too burned down in 1916, almost nine months before the Tocaloma fire, but that's a story for another day.

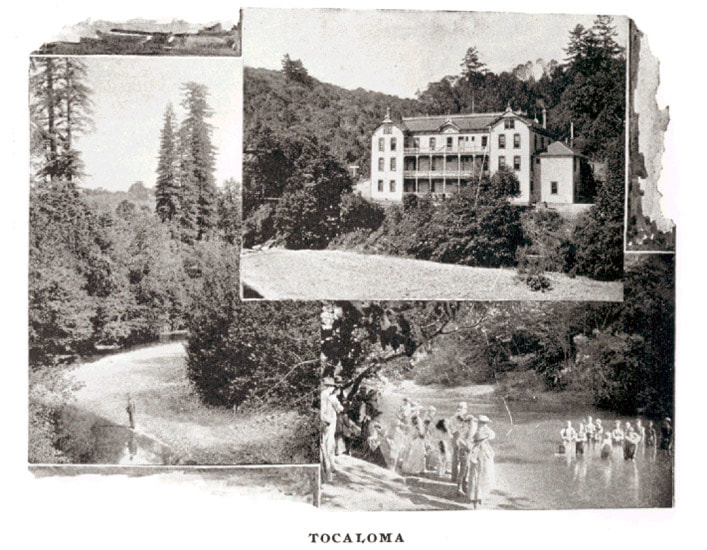

The photo above and the first one below is courtesy of Dewey Livingston, and originally courtesy of the late Rae Codoni. Thanks also to the Anne T. Kent California History Room of the Marin County Free Library, and the California Digital Newspaper Collection for access to the related articles and images from historical newspapers.

So where the heck is Tocaloma? Historian and Author Dewey Livingston has been a good friend to the Marin County Fire History project, and has graciously agreed to share an excerpt about Tocaloma from his upcoming book. We asked him for this since we are guessing most readers will be unaware this place even existed. Thanks Dewey! The link to our project is not only with several historical fires in that immediate area, but also the fact that Tocaloma was the birthplace in 1887 of Marin County Fire Department Chief Sam Mazza, who tragically died in the Line of Duty at a fire in Nicasio in 1948. His story can be found under our Line of Duty Deaths menu.

It is important to view historical fires in the context of the time and place in which they happened. 1916 was two years after World War I started, although America would not enter the conflict until the following year. Marin County had a population of only about 10% of what it is today, or 26,000 people spread over the vast area. Very few of the roads were paved back then, but were was railroad service linking most populated areas, including right next to where this fire was. The Northwestern Pacific Railroad line ran up the Ross Valley, came through the Bothin Tunnel linking Fairfax and Woodacre, continued out to Point Reyes Station, and went on up to Cazadero in Sonoma County. The Golden Gate Bridge would not exist for another 21 years, and the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge was not in service for another 40 years. The Mt. Tamalpais and Muir Woods Railroad was very much in business, including the Tavern of Tamalpais, which would burn down in 1923. Read about that under our Major Fires, Incidents menu>Structure Fires, 1923.

While the short-lived Tamalpais Fire Association had formed a few years prior, the Tamalpais Forest Fire District would not be organized until the following year. The Marin County Fire Department did not exist until 1941, after the TFFD ended. The fire departments operating at that time included Sausalito, Mill Valley, Corte Madera, Larkspur, Ross, San Anselmo, Fairfax, San Rafael, San Quentin, and Novato. Almost all of the firemen were volunteers, usually working and living in the towns where they served. Motorized apparatus was in its infancy, with the first motor-driven chemical engine known to be purchased coming to Ross in 1910. Fire hose carts and wagons were still in use, and water systems were limited. Firefighting at that time still included community members willingly jumping in to help save furniture and belongings from burning structures, with most buildings usually burning to the ground within a few hours.

The name Tocaloma is believed to be of Miwok Indian origin, with the ending suggesting -yome, meaning "place", where an Indian village may have been located. The nearby stream was once called Arroyo Tokelalume, and the Central Sierra Miwok language included tokoloma, meaning "land salamander." Did you know that Tocaloma is just 1/2 mile west down the dirt road, creek, and rail line from the Pioneer Paper Mill that Samuel P. Taylor built in 1856? It was a huge structure, and the very first paper mill on the entire West Coast of America, supplying paper to businesses such as all of the major newspapers of the day. Sadly, it too burned down in 1916, almost nine months before the Tocaloma fire, but that's a story for another day.

The photo above and the first one below is courtesy of Dewey Livingston, and originally courtesy of the late Rae Codoni. Thanks also to the Anne T. Kent California History Room of the Marin County Free Library, and the California Digital Newspaper Collection for access to the related articles and images from historical newspapers.

|

A Place Called Tocaloma

by Dewey Livingston Excerpt from Historian and Author Dewey Livingston’s book about the Point Reyes area, due Spring of 2018. “TOCALOMA! called the musical voice of the conductor as the train stopped at a little depot a short distance beyond Taylorville,” wrote a visitor in 1890. This little hamlet, a couple of miles east of Olema on the banks of Lagunitas Creek, didn’t find its way into Bay Area consciousness until more than a decade after the North Pacific Coast Railroad came through and it became a resort region. As time went by, Tocaloma retreated into obscurity, only to become part of the common local language again in the 2000s when various newsworthy events occurred there. This “blink and you’ll miss it” place has a fascinating and surprisingly rich history. This paper tells the story of the Tocaloma Hotel. |

Tocaloma as a popular resort

While the local dairy ranches gave a sense of stability to the area, it soon became a popular place for visitors, especially hunters and fishermen. The arrival of the North Pacific Coast Railroad in 1875 solidified the position of Tocaloma in Marin County, with a depot that served nearby Olema and official place name of its own. Now a crossroads—with rail, the main road from San Rafael to Olema and beyond, and another road leading north and east to Petaluma—it proved to be a fine place for a roadhouse catering to sportsmen.

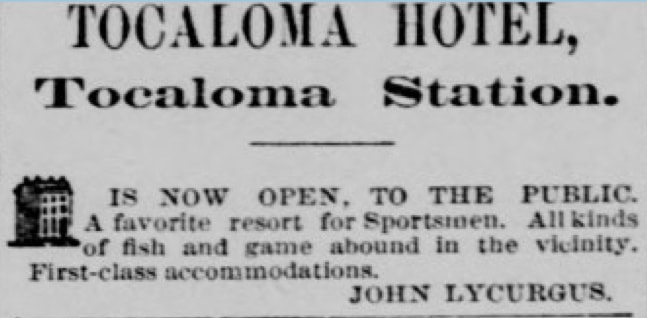

It was a Greek named John Lycurgus who breached the Swiss sensibility of the place. In 1879, across from the Giuseppe Codoni ranch, he built the Tocaloma House, a two-story hotel “furnished with every comfort for guests” and featuring what they called a Swiss Bowling Alley. “It is situated in the very midst of the finest sporting district to be found anywhere near the city,” reported the San Rafael paper, “its streams abounding with fish and its hills with game…. Tocaloma will be the destination of many Nimrods and Waltons next week.”

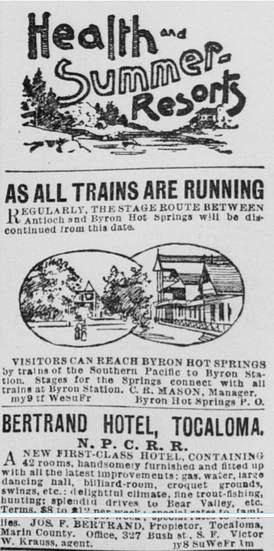

Lycurgus passed the business to one Joseph Adams in 1882, and three years later it burned. The site had been so successful that a rebuild was required, and Frenchman Joseph Bertrand arrived for the job. Bertrand spent a reported $25,000 on a fine hotel that opened in 1889. Building contractor N. O. Anderson, who operated a blacksmith shop in Bolinas, built a structure as large and elaborate as any seen in western Marin to that date; the San Francisco Call deemed it “handsome” and that was an understatement.

While the local dairy ranches gave a sense of stability to the area, it soon became a popular place for visitors, especially hunters and fishermen. The arrival of the North Pacific Coast Railroad in 1875 solidified the position of Tocaloma in Marin County, with a depot that served nearby Olema and official place name of its own. Now a crossroads—with rail, the main road from San Rafael to Olema and beyond, and another road leading north and east to Petaluma—it proved to be a fine place for a roadhouse catering to sportsmen.

It was a Greek named John Lycurgus who breached the Swiss sensibility of the place. In 1879, across from the Giuseppe Codoni ranch, he built the Tocaloma House, a two-story hotel “furnished with every comfort for guests” and featuring what they called a Swiss Bowling Alley. “It is situated in the very midst of the finest sporting district to be found anywhere near the city,” reported the San Rafael paper, “its streams abounding with fish and its hills with game…. Tocaloma will be the destination of many Nimrods and Waltons next week.”

Lycurgus passed the business to one Joseph Adams in 1882, and three years later it burned. The site had been so successful that a rebuild was required, and Frenchman Joseph Bertrand arrived for the job. Bertrand spent a reported $25,000 on a fine hotel that opened in 1889. Building contractor N. O. Anderson, who operated a blacksmith shop in Bolinas, built a structure as large and elaborate as any seen in western Marin to that date; the San Francisco Call deemed it “handsome” and that was an understatement.

|

The 42-room hotel was rather imposing, with a full three stories and additional attic space. Decorative spires adorned each gable end and fine woodwork was seen both inside and out. The hotel’s two wide balconies faced the scenic creek while the North Pacific Coast Railroad delivered passengers to the equally fine west side, their tracks only steps from the entrance.

Bertrand also had several cottages constructed, and provided cleared areas in the adjacent woods for camping. Water came piped from a spring on the hill, and gas for lighting was manufactured on site. Guests found entertainment in the large dance hall and challenged new and old friends in the billiard rooms. An elegant kitchen and dining room fed scores of guests, who could linger and enjoy the site or travel out on foot, train or stagecoach in all directions. Hotel patrons spent anywhere from a single night to the full summer at the comfortable hostelry, paying $8 to $12 per week, with special rates for families. Its restaurant and bar were open to the public, and renowned. |

There was plenty to do in and around Tocaloma in the 1890s. Fishermen headed up or down the creek and sought out good pools and active tributaries for the steelhead trout and salmon. Hunters took to the hills, with permission of nearby ranchers, for bucks, birds and assorted “varmints.” Hikers “tramped” here and there, to the ocean, the mountaintops or merely finding a quiet glade for a picnic. Swimming was perfect on the hot summer days. Stage service took passengers to “splendid” Bear Valley, the lighthouse and other popular destinations like Bolinas or Willow Camp. The train delivered hotel guests on day trips to Camp Taylor, Point Reyes Station, Millerton and Marshall.

Or, if a party wanted to stay close, the grounds featured typical Victorian entertainments like croquet courts and swings, as well as short hiking trails with “rustic benches and tables for lunching parties … scattered at convenient intervals.” Train service to Tocaloma appears to have been scheduled for the convenience of visitors, especially the mostly male family members who worked in the city. “The trains will prove a great convenience to those business men whose families will spend the summer in Marin County,” wrote the Call. An early train left Tocaloma at 6:50 a.m., depositing passengers in San Francisco at 8:45; they returned on the 5:00 train, arriving at the hotel by 7:10 in time for dinner.

Mssr. Bertrand’s Tocaloma Hotel hosted grand balls, well publicized in Marin County and San Francisco. For instance, a “special ball” in July of 1891 featured Blum’s Orchestra from San Francisco. “Dr. Deas and Miss Maud Garcia led the grand march, in which some seventy couples participated,” reported the Call. “During the intervals of dancing the Misses Plagemann of this city rendered some choice vocal selections.” In a dancing contest, the winners were presented with a silver medal and a diamond breastpin.

The hotel was busy throughout its heyday from 1890 into the 20th century. During one day during the summer of 1895 Bertrand’s hotel showed on its guest register 12 families, 11 couples and 34 individuals, probably about 100 people.

It attracted organized groups, such as the Annual Outing of the Harmonie Society of San Francisco, which, in 1892, chartered a special train and “gathered in the woods at Tocaloma Saturday night to witness the occultation of Mars,” according to the San Francisco Call. It was a fun-loving group of wealthy immigrant German businessmen: “In the absence of telescopes inverted beer-glasses were used to observe the rare astronomical event.”

Bertrand and his “comely wife and pretty daughter” made ready for the group, preparing a feast and decorating the hotel with Japanese lanterns and bunting. The full train’s arrival was noted by the Call correspondent: To the tune of “Ta-ra-ra-boom-de-ray” the songsters stepped from the train into the dining-room. Here the menu and the decorations were splendid. Redwood boughs, ferns and beautiful wildflowers hid the bare walls and covered that part of the tables not occupied by the fricasse chicken and sundry long black bottles. “Hurrah for the host! hurrah for the committee! hurrah for everybody” cried the songsters. Then they fell to and made the viands look sick and the bottles empty.

Members of the Harmonie Society were proud of their musicality.

“The wild woods rang with merriment, and the hillsides echoed and re-echoed the happy voices and clinking glasses,” wrote the scribe in the Call. “You never saw a merrier crowd of staid business men in all your life [who] passed the hours till midnight in song and unalloyed fun.” The next morning the large group left for a picnic in Bear Valley, with a visit to the ocean bluffs. “Every wagon and stage in the country for miles around was pressed into service, and behind the gay procession came the lunch-wagon.” The luncheon featured “Tocaloma salads” and cold chicken legs—“and there was something to wash it down with, too.” The happy men returned to the hotel for dinner and more songs, only to return to work early the next morning.

Or, if a party wanted to stay close, the grounds featured typical Victorian entertainments like croquet courts and swings, as well as short hiking trails with “rustic benches and tables for lunching parties … scattered at convenient intervals.” Train service to Tocaloma appears to have been scheduled for the convenience of visitors, especially the mostly male family members who worked in the city. “The trains will prove a great convenience to those business men whose families will spend the summer in Marin County,” wrote the Call. An early train left Tocaloma at 6:50 a.m., depositing passengers in San Francisco at 8:45; they returned on the 5:00 train, arriving at the hotel by 7:10 in time for dinner.

Mssr. Bertrand’s Tocaloma Hotel hosted grand balls, well publicized in Marin County and San Francisco. For instance, a “special ball” in July of 1891 featured Blum’s Orchestra from San Francisco. “Dr. Deas and Miss Maud Garcia led the grand march, in which some seventy couples participated,” reported the Call. “During the intervals of dancing the Misses Plagemann of this city rendered some choice vocal selections.” In a dancing contest, the winners were presented with a silver medal and a diamond breastpin.

The hotel was busy throughout its heyday from 1890 into the 20th century. During one day during the summer of 1895 Bertrand’s hotel showed on its guest register 12 families, 11 couples and 34 individuals, probably about 100 people.

It attracted organized groups, such as the Annual Outing of the Harmonie Society of San Francisco, which, in 1892, chartered a special train and “gathered in the woods at Tocaloma Saturday night to witness the occultation of Mars,” according to the San Francisco Call. It was a fun-loving group of wealthy immigrant German businessmen: “In the absence of telescopes inverted beer-glasses were used to observe the rare astronomical event.”

Bertrand and his “comely wife and pretty daughter” made ready for the group, preparing a feast and decorating the hotel with Japanese lanterns and bunting. The full train’s arrival was noted by the Call correspondent: To the tune of “Ta-ra-ra-boom-de-ray” the songsters stepped from the train into the dining-room. Here the menu and the decorations were splendid. Redwood boughs, ferns and beautiful wildflowers hid the bare walls and covered that part of the tables not occupied by the fricasse chicken and sundry long black bottles. “Hurrah for the host! hurrah for the committee! hurrah for everybody” cried the songsters. Then they fell to and made the viands look sick and the bottles empty.

Members of the Harmonie Society were proud of their musicality.

“The wild woods rang with merriment, and the hillsides echoed and re-echoed the happy voices and clinking glasses,” wrote the scribe in the Call. “You never saw a merrier crowd of staid business men in all your life [who] passed the hours till midnight in song and unalloyed fun.” The next morning the large group left for a picnic in Bear Valley, with a visit to the ocean bluffs. “Every wagon and stage in the country for miles around was pressed into service, and behind the gay procession came the lunch-wagon.” The luncheon featured “Tocaloma salads” and cold chicken legs—“and there was something to wash it down with, too.” The happy men returned to the hotel for dinner and more songs, only to return to work early the next morning.

|

During this period in the mid-1890s, the Tocaloma Hotel attracted bicyclists from the city, who rode in organized and sponsored groups like the Bay City Wheelmen, Pacific Cycling Club (whose dozen members had “a pleasant ride and an excellent dinner” in 1890), Camera Club Cyclists and the Olympic Club’s cycling annex. Tocaloma offered good food and lodging and so the cyclists came, called in one article the “able-bodied knights of the rubbered wheel.”

|

Bertrand sold the hotel to San Francisco chef Caesar Ronchi in 1913. Caesar was somewhat of a fabled character, having fled from San Francisco that May after informing on members of an “Italian bunko gang,” leading to the indictment of eight men with whom he had formerly been associated. Ronchi got a letter with a skull and crossbones reading, “Beware —the gang ballotted on you last night. A word to the wise is sufficient. You know what is to be the fate of all traitors. Signed, Black Hand.” A frightened Ronchi pleaded with the police for protection but, as the newspaper reported “the police would rather see him out of the way, so he will get little protection.” Ronchi and his wife Isolina settled in at Tocaloma, hoping it would be out of sight, but he soon became a local celebrity for his engaging personality, not to mention his fine food and drink.

|

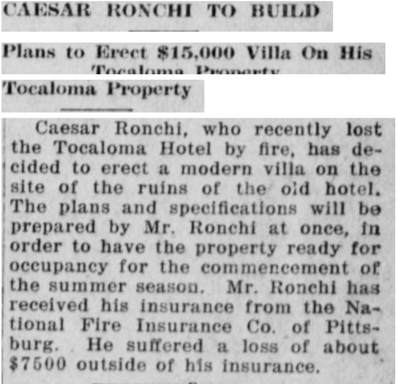

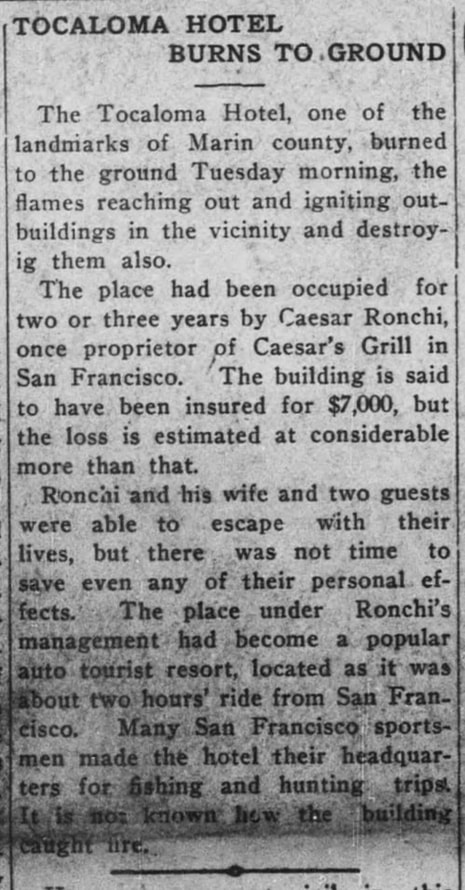

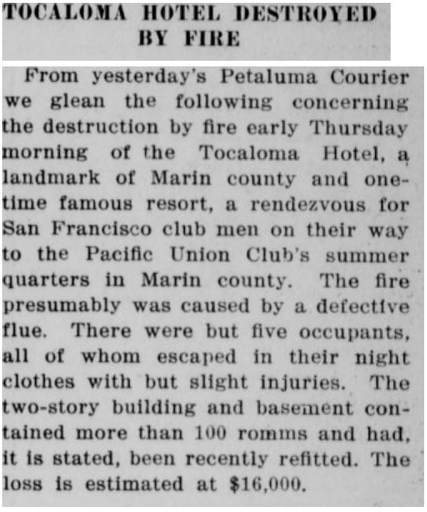

Who knows if his tormenters finally got to him—but a mysterious fire destroyed the venerable hotel on December 26, 1916. [see article below]

Ronchi quickly announced plans to rebuild a $15,000 replacement, only half of which would be covered by insurance. He had a smaller building constructed on the same site, a tavern with a steep sloping roof and no hotel rooms. Caesar’s Tavern opened in May of 1917. The place was reportedly a good spot for a drink during prohibition, and when Sir Francis Drake Highway opened in 1929, a steady stream of motorists adopted Caesar’s as a regular stop on their way to the coast through the 1930s. |

Neighboring rancher Don McIsaac noted that Ronchi sang opera, his voice heard down the road at the ranch. Historian Jack Mason wrote that Caesar “was a portly Italian tenor whose connection with the world of grand opera was as nebulous as his reputed alliance with San Francisco’s prohibition gangland.” Caesar’s became a private residence and over the past decades, largely abandoned, it has fallen into ruin. The forgotten Tocaloma bridge sits silently as its neighbor, but the solid old concrete bridge will surely outlive Caesar’s Tavern.