The San Quentin State Prison Jute Mill burned in 1909, and a convict fighting the fire was killed. Story below, more coming.

Jute is a long, soft, shiny vegetable fibre that can be spun into coarse, strong threads. It was and is today one of the most affordable natural fibers and is second only to cotton in amount produced and variety of uses of vegetable fibers. Jute fibers are composed primarily of the plant materials cellulose and lignin. Jute is also called "the golden fiber" for its color and high cash value.

Jute is the second most important vegetable fiber after cotton due to its versatility. Jute is used chiefly to make cloth for wrapping bales of raw cotton, and to make sacks and coarse cloth. The fibers are also woven into curtains, chair coverings, carpets, area rugs, hessian cloth, and backing for linoleum.

More than a billion jute sandbags were exported from Bengal to the trenches during World War I and also exported to the United States southern region to bag cotton. It was used in the fishing, construction, art and arms industries.

While jute is being replaced by synthetic materials in many of these uses, some uses take advantage of jute's biodegradable nature, where synthetics would be unsuitable. Examples of such uses include containers for planting young trees, which can be planted directly with the container without disturbing the roots, and land restoration such as occurs following wildfires where jute cloth prevents erosion occurring while natural vegetation becomes re-established.

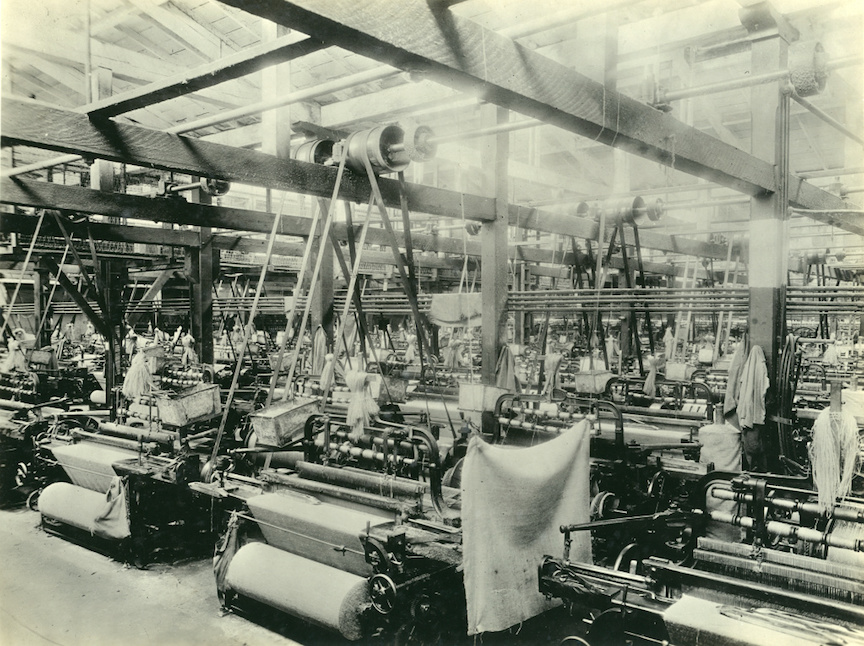

The jute mill at San Quentin opened April 3, 1882. During its first year of operation the jute mill helped cut in half the $200,000 cost of operating San Quentin. According to various historical sources, the jute mill became the focal point for infection spread by the dust, resulting in mass mutinies by the prisoners and in graft and corruption among the managers. This Jute Mill would supply sand bags not only for use in World War I, but in World War II and Korea.

Jute is the second most important vegetable fiber after cotton due to its versatility. Jute is used chiefly to make cloth for wrapping bales of raw cotton, and to make sacks and coarse cloth. The fibers are also woven into curtains, chair coverings, carpets, area rugs, hessian cloth, and backing for linoleum.

More than a billion jute sandbags were exported from Bengal to the trenches during World War I and also exported to the United States southern region to bag cotton. It was used in the fishing, construction, art and arms industries.

While jute is being replaced by synthetic materials in many of these uses, some uses take advantage of jute's biodegradable nature, where synthetics would be unsuitable. Examples of such uses include containers for planting young trees, which can be planted directly with the container without disturbing the roots, and land restoration such as occurs following wildfires where jute cloth prevents erosion occurring while natural vegetation becomes re-established.

The jute mill at San Quentin opened April 3, 1882. During its first year of operation the jute mill helped cut in half the $200,000 cost of operating San Quentin. According to various historical sources, the jute mill became the focal point for infection spread by the dust, resulting in mass mutinies by the prisoners and in graft and corruption among the managers. This Jute Mill would supply sand bags not only for use in World War I, but in World War II and Korea.

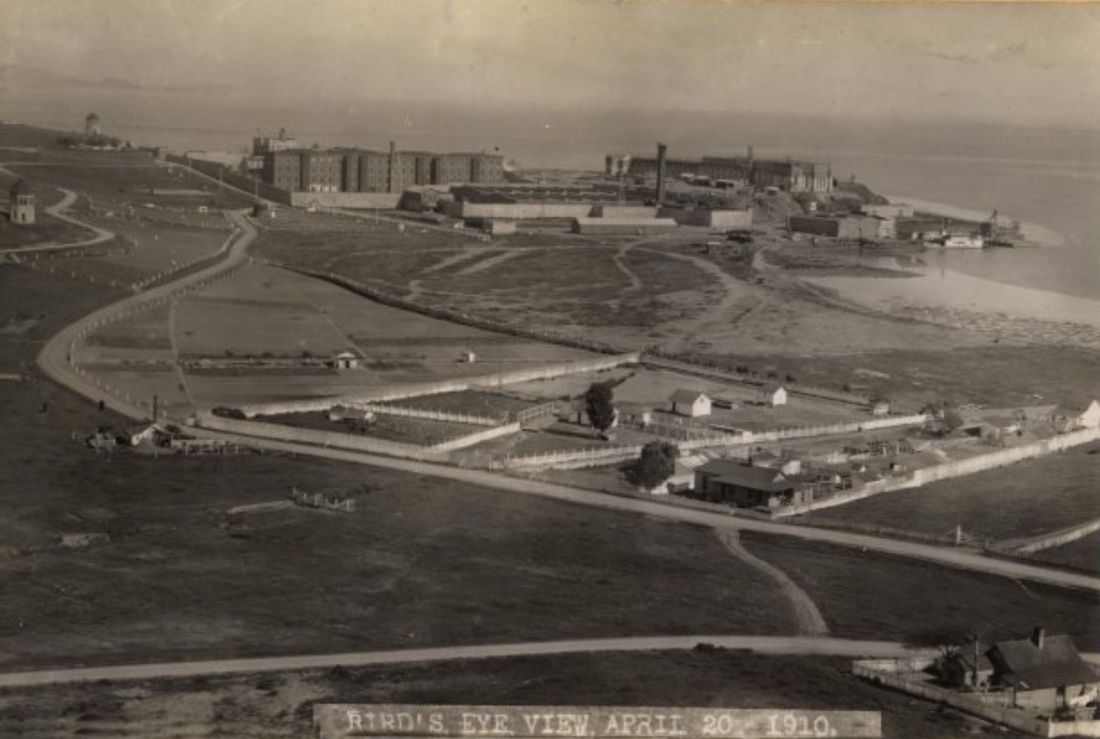

As reported in the April 3, 1910 edition of the San Francisco Call, Volume 107, Number 124:

"...Under his administration his prison officials seem to take much the same position. For instance, when the warden was up at Sacramento something over a year ago the big Jute warehouse down on the water front outside the wails took fire one morning. It was a terrible blaze — on a wharf, under the hill, out of range of gatling guns, etc. The convict fire brigade and several hundred other prisoners were taken out and sent to fight the fire.

In all 600 men — some of them decidedly dangerous men if handled as such men are usually handled — risked their lives to extinguish the thing. One convict fell from a burning beam and lost his life. Some 20 or 30 were overcome by smoke and had to be carried by their comrades to the hospital.

All the time it was like all fire fighting — men rushing hither and thither, bawling orders, breathing stifling smoke, plunging into wreaths that hid them, moving swiftly always — vast confusion — 300 convicts out at once and possibly 20 guards — all the guards being kept as busy as the convicts. And when it was over every one of those prisoners went back to his cell tired out, some of them utterly exhausted, many badly burned, others with lungs sore from smoke.

They went back to their cells and no one but did it; none tried to escape. There was another occasion when six men upset a boat out in the bay. A number of the convicts were allowed to strip and swim out in an attempt to rescue them. And that night convicts dived for hours to recover two of the bodies. The convicts themselves, are the ones— who like best to tell of these incidents. They seem to hold a sort of pride in them. A sort of pride is a fine thing to produce esprit de corps. Esprit de corps sounds queerly when one is talking about a prison."

"...Under his administration his prison officials seem to take much the same position. For instance, when the warden was up at Sacramento something over a year ago the big Jute warehouse down on the water front outside the wails took fire one morning. It was a terrible blaze — on a wharf, under the hill, out of range of gatling guns, etc. The convict fire brigade and several hundred other prisoners were taken out and sent to fight the fire.

In all 600 men — some of them decidedly dangerous men if handled as such men are usually handled — risked their lives to extinguish the thing. One convict fell from a burning beam and lost his life. Some 20 or 30 were overcome by smoke and had to be carried by their comrades to the hospital.

All the time it was like all fire fighting — men rushing hither and thither, bawling orders, breathing stifling smoke, plunging into wreaths that hid them, moving swiftly always — vast confusion — 300 convicts out at once and possibly 20 guards — all the guards being kept as busy as the convicts. And when it was over every one of those prisoners went back to his cell tired out, some of them utterly exhausted, many badly burned, others with lungs sore from smoke.

They went back to their cells and no one but did it; none tried to escape. There was another occasion when six men upset a boat out in the bay. A number of the convicts were allowed to strip and swim out in an attempt to rescue them. And that night convicts dived for hours to recover two of the bodies. The convicts themselves, are the ones— who like best to tell of these incidents. They seem to hold a sort of pride in them. A sort of pride is a fine thing to produce esprit de corps. Esprit de corps sounds queerly when one is talking about a prison."

See below - Retired Larkspur Fire Chief and Historical Committee member Bill Lellis discovered the convict's name in April of 2016 through newspaper research. See the Line of Duty Deaths Menu>1909 for more information.

Sacramento Union, Number 13, 6 March 1909

"INJURED CONVICT DIES.

SAN QUENTIN (Cal.), March 5.

S. J. Frooman, the convict who broke his leg and was otherwise badly crushed while fighting the fire that threatened the destruction of the state penitentiary here last Wednesday, died today as a result of his injuries. Frowman was injured while dragging a gattling gun of of the flames."

Sacramento Union, Number 13, 6 March 1909

"INJURED CONVICT DIES.

SAN QUENTIN (Cal.), March 5.

S. J. Frooman, the convict who broke his leg and was otherwise badly crushed while fighting the fire that threatened the destruction of the state penitentiary here last Wednesday, died today as a result of his injuries. Frowman was injured while dragging a gattling gun of of the flames."