Fireworks, Rockets, Explosions,

and Fires, Oh My!

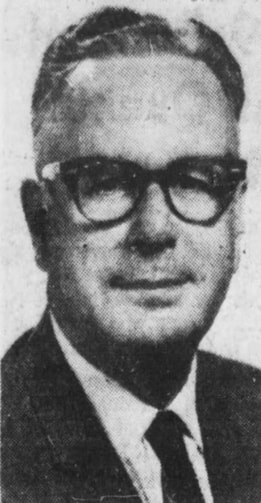

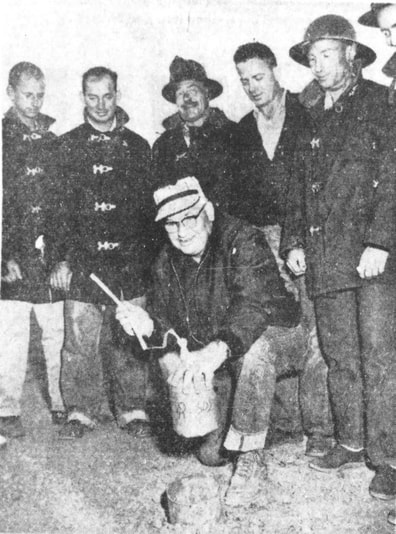

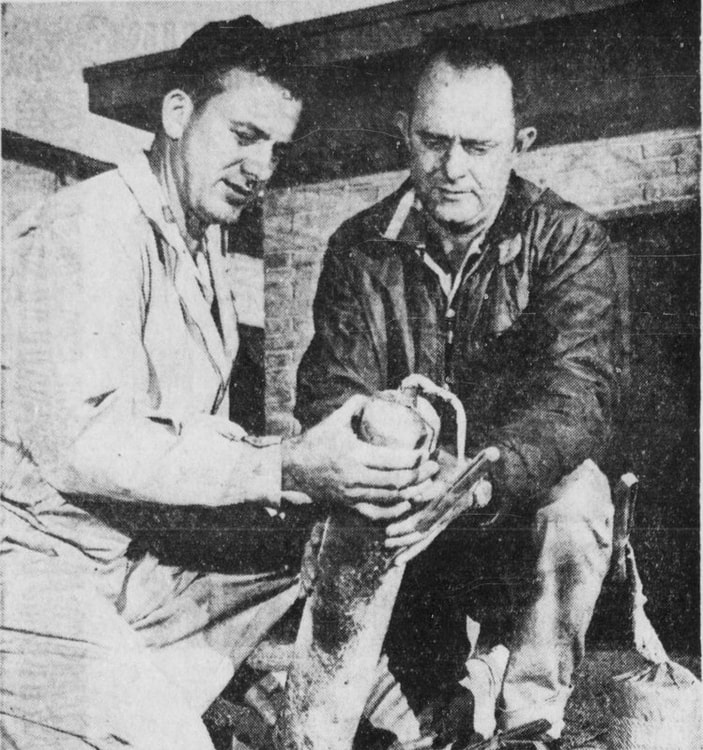

Corte Madera Volunteer Fire Department Ltd. Fireman Carl K. Brown, left, and Assistant Fire Chief Harold Kelly load a "bazooka" with a four-break salute rocket for the community display on July 4, 1960, centered over Corte Madera Town Park. Both were California State Fire Marshal licensed Pyrotechnicians for many years. Photo from CMVFD historical scrapbook collection.

|

by Tom Forster

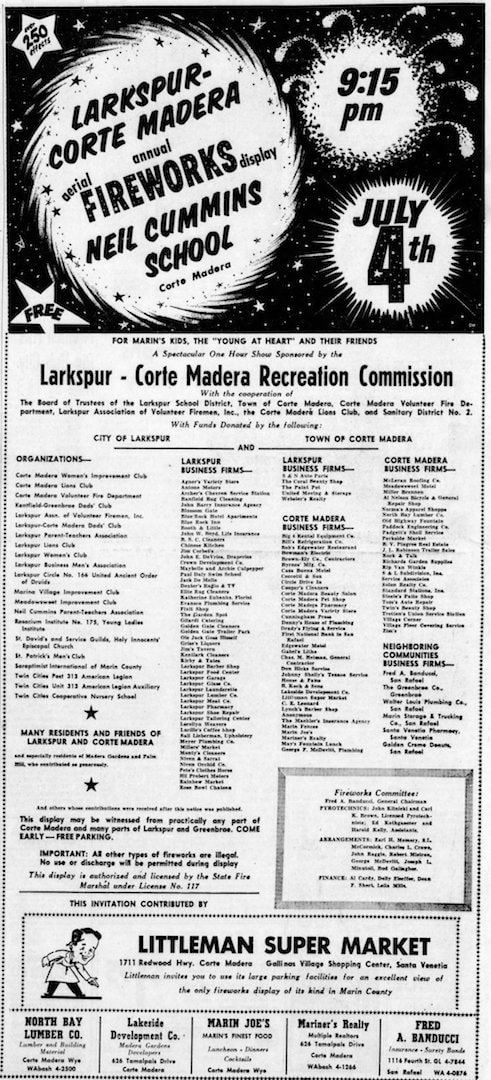

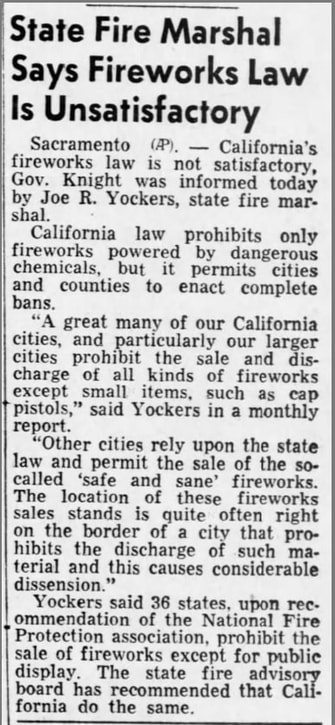

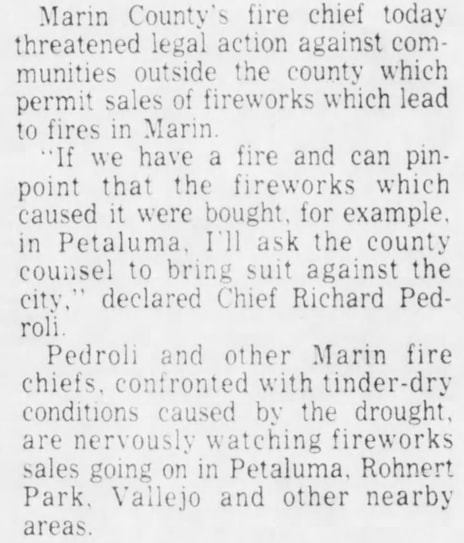

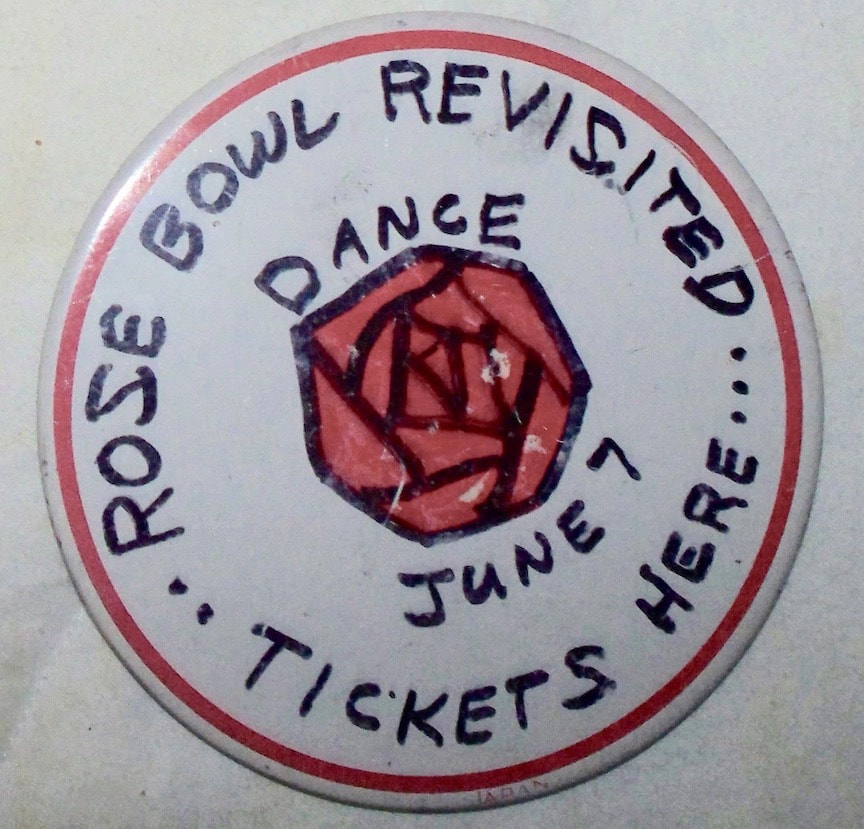

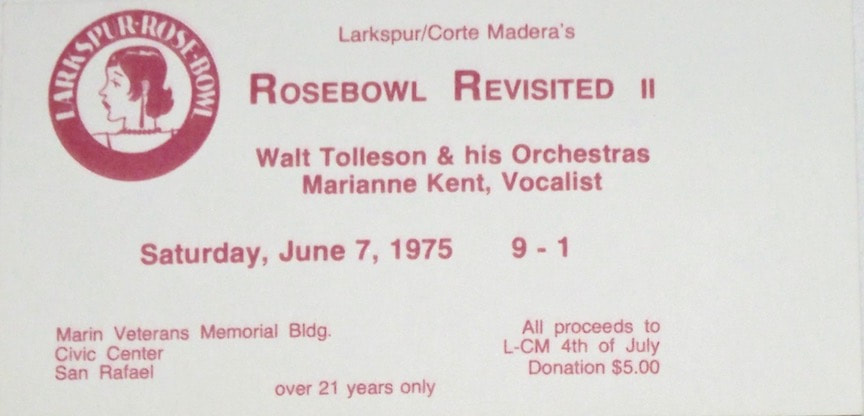

As a young boy growing up in Corte Madera in the 1960’s, I remember the fireworks starting very early in the morning on many July 4th holidays. While all fireworks were illegal by that time in Marin County, abundant explosions would echo throughout the day and night all over the region. Multiple, rapid, and loud snaps of firecracker packs, the deep thud of barrel bombs, the whistle, scream, and crack of bottle rockets, the loud cracks of cherry bombs, the very bright showers of roman candles, and more. Other regular sounds echoing throughout the valley included dogs barking, upset by all the noise, and occasional fire horns and sirens responding to the inevitable grass fires and injuries. The Larkspur and Corte Madera Fire Departments would start the annual Independence Day celebrations a day earlier, the evening of July 3. This was in the tradition of a long-standing “friendly” rivalry between the two communities, dating back to the early 1900’s when the official boundaries were set and there was conflict over who would get the Larkspur Corte Madera School on Magnolia Ave. Varying by year, fire department competitions on July 3 included water fights pushing a barrel on a candle back and forth; a tug-of-war with the losers being dragged through an open stream from a 2 ½” outlet on a fire hydrant; and occasional horseshoe games. On the 4th, following a pancake breakfast in Larkspur at the American Legion Hall, Joe Wagner Baseball Field in Larkspur would be home to the annual, hard-fought Corte Madera FD vs. Larkspur FD softball game, followed by the teams sharing a keg of beer under the bridge behind the backstop. Also on the 4th, the Corte Madera Town Park would fill up with thousands of people enjoying an art show, music, and various food booths clustered around the Corte Madera Lions Club Recreation Center at the Town Park. They’d enjoy a very long, traditional 4th of July parade along Magnolia, Corte Madera, and Tamalpais Avenues, in the shadow of Mt. Tamalpais, grab some food and BBQ, and wait for nightfall before many lit off their own fireworks in the park. Darkness would bring a spectacular aerial fireworks display, originating at Neil Cummins School, adjacent to the Town Park. For many years this was the largest fireworks display in Marin County, attracting from 10,000 to 30,000 additional people into Corte Madera and Larkspur to see the show. It was not the first such community fireworks display in Marin – that honor needs more research but seems to be pointed towards the community of Sausalito, with fireworks starting in the 1890's and still happening today. The Marin County Fair did not exist yet in the 1950's, just the annual Marin Art & Garden Show in Ross, without fireworks. Enforcement of the fireworks regulations prohibiting personal use was minimal back then, in part due to the very small police staffs of the day, and the huge scope of the problem. Living near Chinatown in San Francisco helped create an abundant and cheap supply in Marin County. As time went on and the population grew, there were more and more related problems. Grass fires, injuries, traffic jams, and even the occasional wood shake roof catching on fire, from bottle rockets and other fireworks and embers. We know of a least one major fire in Marin's history caused by fireworks rockets. Much of Sausalito's business district burned up on July 4th in 1893, story coming very soon on this site. Going way back, fireworks were invented during the 7th century in China, and mostly used in festivities. They eventually spread around the world, to regions like America. The very first Independence Day with fireworks happened in 1777, and in 1789, when President George Washington’s inauguration also included fireworks. In the 1950’s, the California State Fire Marshal’s Office was in the process of tightening up fireworks regulations. Many communities had already banned fireworks all together, and most had at least limited their use to so called “safe and sane” devices. The 1950’s and 60's included the tense days of the Cold War with Russia, and America was still testing nuclear bombs above ground. In fact, on the morning of the 4th of July, the U.S. touched off the largest atomic bomb test to date. Several months later on October 1, 1957, the Russians lauched Sputnik, the first successful satellite propelled by a rocket. This event not only kicked the “space race” into high gear, but also led to increased interest in amateur rocketeering, including those lauching fireworks. As the interest grew, so did the related problems, and over the next 15 years there was a major effort to further restrict use. Back to 1952 in Corte Madera, where the success of a neighborhood display by Fred and Elva Banducci and neighbors on Palm Hill led to the idea of doing one large community display. Following up on a suggestion by Betty Klein, Banducci organized the first attempt at a larger community display in Corte Madera in 1953. It was deemed somewhat of a “dud” overall, due to low quality fireworks and the lack of skilled pyrotechnicians. The other problem was finding someone to discharge the fireworks safely and at low cost, given that no insurance company would cover inexperienced pyrotechnicians. The State Compensation Insurance Fund decided to give permission to perform the task to the Corte Madera Volunteer Fire Department Ltd. "in the line of duty." 1954 featured the first successful event with higher quality fireworks. In 1956, a State law was passed requiring large displays to be permitted by the State Fire Marshal's Office (SFM) along with licensing pyrotechnicians. CMVFD, Banducci, and the Lions Club secured one of the first SFM permits in California for such a community display in 1956. For the next 14 years the CMVFD would operate the displays. The Lions Club organized the fund-raising, with money raised from businesses, the Town of Corte Madera and the City of Larkspur, and various community groups. Three CMVFD volunteer firemen (as they were called then) became State Fire Marshal licensed Pyrotechnicians in 1956 – John Kliniecki, Harold Kelly, and Carl K. Brown. Other volunteer firemen served on the fireworks team under their strict supervision, including Harold Wagstaff, Ed Kothgassner, George McDevitt, Bud Gallagher, Jack Forster, William Nelson, Dennis Colthurst, Jim Walker, Tony Moreno, and more. Back then each device required loading by hand into a “bazooka tube”, and then having the fuse lit by hand. It was very dangerous work, performed in careful teams of five or six men. Three would load the shells in bazooka tubes set in the ground, two would light the fuses and fire the rockets, and one would serve as a spotter to make sure each shell went off. It was a hot, smoky, and dirty job, and the teams were very proud of their work. Dealing with any duds and cleaning up the debris was part of the work. This was at a time when alcohol and cigarettes were much more common in society, including during events. While there were rumors over the years about some of the team drinking, the factual record reflects a very safe operation, with no serious injuries during the 14 years in Corte Madera. John Klinieki led the display for CMVFD until 1960, when Harold Kelly and Carl Brown took over for the decade. Kelly was typically the fireworks leader, with Brown representing the Lions Club also and organizing the fund-raising and marketing. Emergency response during the event was provided by the rest of the CMVFD Ltd., and the Larkspur FD. As Marin’s population grew rapidly, the related problems also expanded. The total County population more than doubled from 1950 to 1970, from about 86,000 people in 1950 to more than 208,000 in 1970. In Corte Madera, the large Madera Gardens housing development was built in the 1950’s, along with the Corte Madera Shopping Center, today rebuilt and operating as the Town Center. East Corte Madera was also being developed over the marshlands and in the hills, with commercial and housing developments happening all the way east towards Ring Mountain. Traffic and parking began to be a real problem during the fireworks show, including on Highway 101, delaying emergency responses. Finally, in 1968 the decision was made to move the event to Larkspur, with Kelly supervising Larkspur firemen in the work for the first year. It was thought the location known as Bundy Field, today Piper Park, would be less problematic for many reasons. Several more years of fireworks followed, along with a transition from the Larkspur Volunteer Fire Department to the hiring of a private fireworks company to execute the show. This drove the cost up significantly, since the labor was no longer coming from volunteers. Sadly, an incident occurred in 1971 that led down the path of the eventual end of fireworks in the Twin Cities. Several teenage boys climbed over a fence to explore the area where the fireworks had been set off the night before. They gathered some fireworks debris into a pile and lit it off. The rapid combustion burned two 16-year old boys. A $25,000 lawsuit was filed in February of 1972 for damages against the City of Larkspur, Town of Corte Madera, and Pyrotronics Corp., the company hired to run the display that year. The event then took two years off, due to the lack of a safe location from where the display could be held. Habitually, thousands of people showed up on the night of the 4th each of those two years, expecting shows that never happened. The demand was there, and this led to a volunteer committee being formed to bring them back. Meanwhile, funding challenges to pay for hiring a pyrotechnics company had increased. Committee Chair Shirley Walker of Corte Madera, wife of Corte Madera volunteer fireman and Larkspur Chevron Station owner Jim Walker, led a fund-raising effort in 1974 and 1975. They hosted a "Rose Bowl Revisited" dance, held in 1974 at the closed "Disco" market building at Doherty and Magnolia, that is today the Mt. Tam Racquet Club. The 1975 dance was held at the Marin Veterans Auditorium, after some plumbing issues at the old Disco building made for some serious rest room challenges at the 1974 event. Back by popular demand in 1974-75, the launch area was moved east across Highway 101 to the marshlands, roughly in the area where the Village Shopping Center now stands. However, traffic and other woes continued, including backups on Highway 101 into San Rafael that impacted emergency responses in several jurisdictions With that, the fireworks era came to an end in the Twin Cities in the mid-1970's. The Marin County Fair had also transitioned to the new Marin Center space in San Rafael starting in 1971. The first fairs at the new location were held in October, and then in August, and eventually over the 4th of July holiday as it is today. The first fireworks display at a Marin County Fair was on August 3, 1974, and popularity with the public has resulted in what has now become a long-standing tradition. What about the legality of fireworks and sales in Marin? By 1977, Marin County Fire Chief Richard Pedroli and others were leading the final, successful assault against any sale or use of any fireworks, including "safe and sane." A possibility of filing lawsuits against neighboring communities that still allowed the sale of fireworks, like Petaluma, was raised, if the use could be shown to have caused fires in Marin. Today there are relatively few problems in Marin with illegal use, and enforcement is strong. Fire caused by fireworks in Marin are now rare. Thanks go to the CMVFD Ltd. and all of the other groups who organized some very fun and memorable 4th of July celebrations. It is unlikely we'll see such public fireworks displays ever again in the Ross Valley, for many reasons. Sources: Corte Madera Volunteer Fire Department Ltd. historical collection, the Marin Independent Journal, and the San Anselmo Herald. Rosebowl Revisited images below courtesy of Shirley Walker. |

|