NOTE: if you've read Part's I & II already, scroll down for Part III new content as of May 26, 2017.

*** See the slide show below for the actual Distinguished Service Cross documents for Charles Reilley, and more photos on World War I. ***

Part III:

Charlie Reilley Promotes to Marin County Fire Chief

|

by Tom Forster

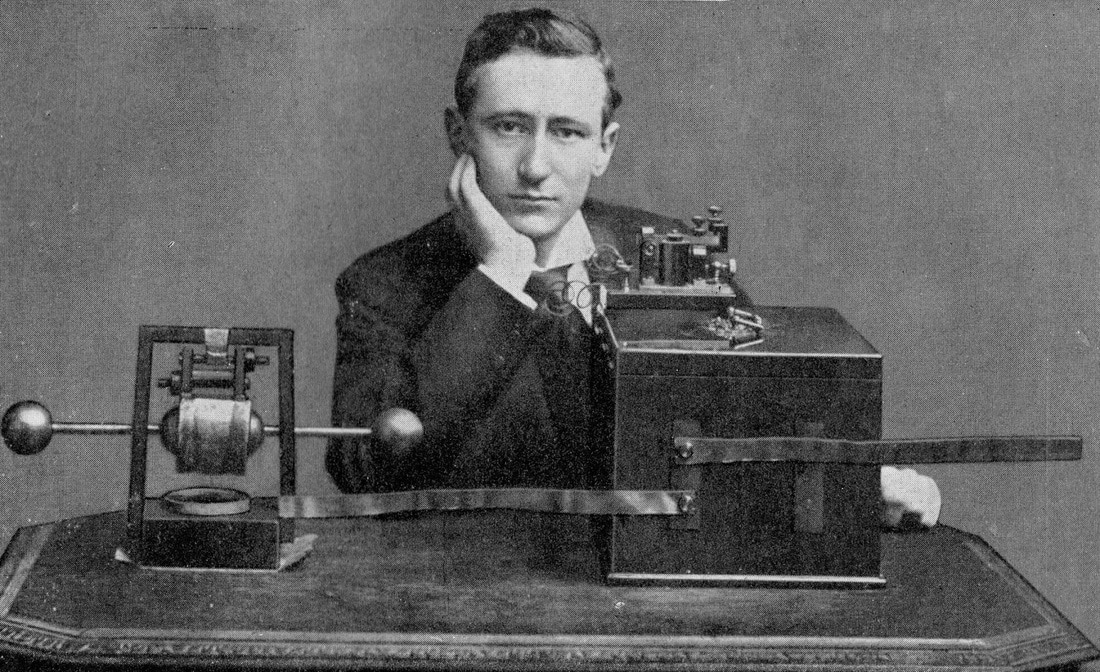

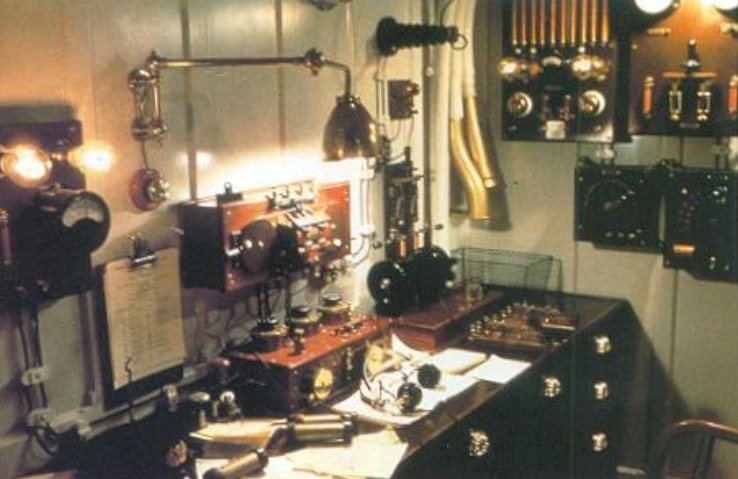

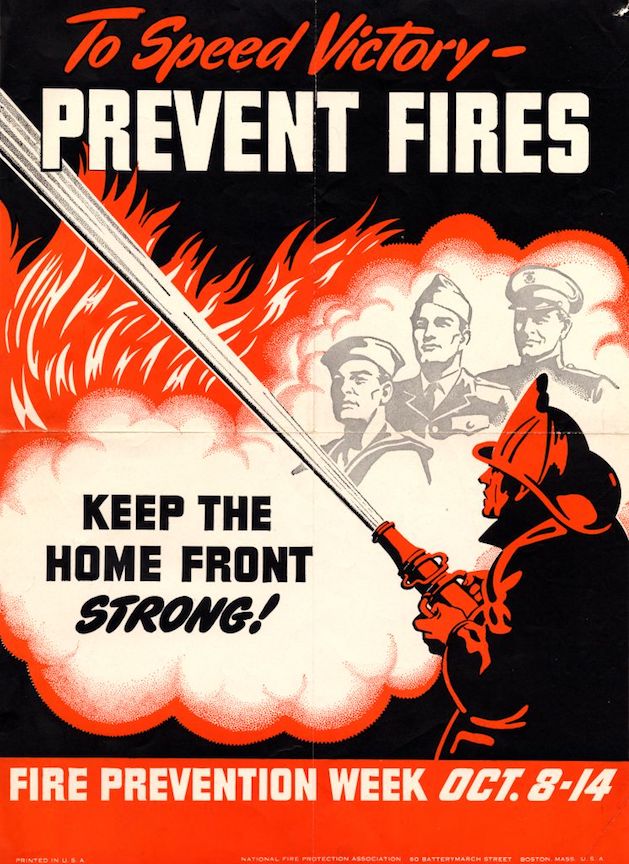

May, 2017 When Charlie Reilley returned from World War I, he first went back to Nevada, where his mother still lived. He later moved to California, where he met his future wife Alice Fountain, while she was working in a department store in San Francisco. They were married on St. Patrick's Day in 1923, and moved to Marin County in 1925, settling down in Point Reyes. Alice was originally from Louisiana, the daughter of Dr. and Mrs. John Fountain of Keatchie, a small rural town near Shreveport. Charlie then went to work as an electrician for the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) in Point Reyes for roughly 20 years. The roots of the RCA operation in Point Reyes began with the arrival of Italian scientist Guglielmo Marconi in America in 1899. Born in Bologna, Italy, in 1874, he was an inventor credited with the foundational work for all future radio communications, later receiving the Nobel Prize for physics. Marconi first began experimenting with Electromagnetic Waves (Radio Waves) in 1894. His first success in sending and receiving Morse code without the use of wires happened in his parents attic, initially transmitting across the room. Three years later, Marconi had increased the transmission distance to 15 miles, and had proven that man-made and natural obstacles did not interfere with the radio waves. Soon after arriving in the U.S., he established the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America, a commercial radio business, aided by a series of successful patent lawsuits against his competitors. He transmitted radio signals across the Atlantic in 1907. This accomplishment eventually gave America and Europe regular wireless, commercial communications, and eventually was used on a much wider scale worldwide. In 1909, Marconi was awarded the Noble Prize for Physics, jointly with Karl Ferdinand Braun, "in recognition of their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy." Three years later he would be credited by the British with helping save the 712 survivors of the Titanic disaster due to the new radio system. The U.S. government, however, felt the opposite. In their view, the limitations and patent driven control of Marconi's system contributed to the loss of life on that dark night. This became the start of what would eventually become a takeover of his company in America. By 1912, Marconi had aquired, through a lawsuit and merger, over 70 land-based radio stations and more than 500 ship-board installations. One was Station KPH, San Francisco’s first radio station. In order to achieve a powerful enough signal to cross the Pacific Ocean, a new, stronger station was built on the Marin County Coastline. All of Marconi’s transoceanic radio stations were “duplex”, or geographically separated complexes for transmitting and receiving. The geographic separation was necessary since the noise of transmission obstructed clear reception. By 1914, Marin had a new transmitting station in Bolinas overlooking the Pacific Ocean, and a new receiving station in Marshall, on the hill overlooking Tomales Bay. These two locations formed the "KPH" Pacific Rim radio station, and were the foundation for the most successful and powerful ship-to-shore communications of that era. KPH also broadcast news, weather and other general information to the shipping community, including relaying business and personal messages to and from ships. Station operators monitored the international distress frequencies for calls from ships in trouble. The business became a big success. However, World War I and the recognition of the strategic importance of radio communication led to the U.S. government securing control over the business. In 1920, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) was formed, after buying the holdings of the American Marconi Company. RCA soon sold the majority of undeveloped land at the Marshall site, retaining only 62.7 acres surrounding the station buildings. After being hired by RCA, Charlie's initial career after the Army would be spent supporting the operations in Bolinas, Marshall, and Point Reyes. In 1923, Marconi developed a short-wave beam system. This was used for more effective long distance communication, and for guiding ships safely into port even in dense fog. The operation at Marshall (which was a long-wave station) was relocated across Tomales Bay to the Point Reyes Peninsula for better short-wave reception. The Marshall station, which is now a State Historic Park, was replaced by a new Art Deco-designed facility located on "G" ranch, near what is known today as North Beach in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. With the decline of Morse code, and improved ship and satellite technology, the station was retired in the late 1990s. The combination of the transmitting (Bolinas) and receiving station (Point Reyes) may be the last intact Marconi-era coast stations in North America. In the early 1930's, Charlie Reilley became a member of the Point Reyes Volunteer Fire Department, and he later also joined the neighboring Olema Volunteer Volunteer FD. Both worked closely with the Tamalpais Forest Fire District Wardens, one of whom was based in Point Reyes. The TFFD was a small but proud organization that began in 1917, primarily designed to protect the wildland areas in Marin. TFFD employed fire wardens, often responding alone out of their home with their own personal pickup truck, for relatively low pay and some reimbursement of expenses. The 1930’s included a gradual transition in their apparatus, with the district purchasing slightly larger trucks and making some necessary modifications. These were primarily heavy duty ‘pickup‘ trucks, or 1-to-1.5 ton trucks with small pumps, fire hose, hand tools, and a water tank added. However, district funding was very minimal, with little support for more features. After all, the 1930’s were dominated by the Great Depression, and war was feared to be on the horizon. By the late 1930’s, two major events hit the district hard. First, the original and long-time Chief Fire Warden Edwin Burroughs Gardner died in 1936. His son Edwin F. Gardner became the next TFFD Chief. Second, In 1939, the State Legislature changed some statewide regulations concerning special districts. Somehow in this process the TFFD was dropped from the State approved special districts list, but never notified. It was apparently a mistake, with the State bureaucrats believing that TFFD no longer existed. Almost two years later, the Town of San Anselmo considered dropping out of the forest fire district, in large part because the City of San Rafael had recently dropped out to save money, by not paying the required forest fire district fees. The rationale was that the incorporated communities were already paying for their own fire departments, and had no need to pay for a service covering the unincorporated areas. When the San Anselmo Town attorney dug into how to withdraw from the district, he discovered the mistake the State had made. Updated legislation was then hastily drawn up and implemented to make TFFD legal again by early 1941, but with several more communities now not wanting to pay for the operation of the district, plans were made to shift the fire protection services to the County. Curiously, the extra fees for some of the Marin County incorporated communities would continue until 1969, when the unincorporated communities governed by the County, and the state covered all MCFD costs. Over 55 years later, a similar and controversial tax called the State Responsibility Area (SRA) fee would return, but that's a story for another day, and one still being litigated in the courts. Throughout their history, TFFD was really at a great disadvantage to do much about working structure fires, due to their apparatus, equipment, and training being focused on grass, brush, and timber fires. So, when homes also burned they were sometimes criticized for doing what appeared to be little to save them. This pattern would continue for the first few decades of the Marin County FD. Given severe financial limitations and other issues, the Tamalpais Forest Fire District ceased operation and dissolved as an organization in June of 1941. The new Marin County Fire Department began on July 1, 1941. The existing TFFD staff, facilities, and equipment were all transferred to the County, including the role of Fire Chief E.F. Gardner. In effect, it was the same department with the same budget, staff, and equipment. Just the governance had changed. Five months later, Pearl Harbor was attacked, and America entered World War II. Locally, Civil Defense became the priority until the war ended, and even afterwards, as the Cold War with the Soviet Union ramped up. MCFD began handling, in practical effect, a broader mission through the 1940's, but with the same equipment and limitations. Building new fire trucks for local government during war time was generally prohibited, due to the war effort needing all the materials needed, such as steel, motors, and rubber. Meanwhile, Charlie Reilley was hired in 1945 as a Fire Warden in Point Reyes for the four-year old Marin County Fire Department (MCFD), and then as a Deputy Sheriff in 1950. He promoted to Fire Chief of the Marin County Fire Department in February of 1951. Authors note: What follows is a very brief, related history of the Marin County FD from their start in 1941, until the early 1950's. This is to provide the background on what Charlie Reilley was faced with in early 1951 when he promoted to Fire Chief. All of the MCFD Fire Chiefs will eventually have biographies, and the department history will be expanded on for the MCFD history page. Thanks to MCFD historians Pete Martin and Greg Jennings, both retired Senior captains, for sharing photographs.

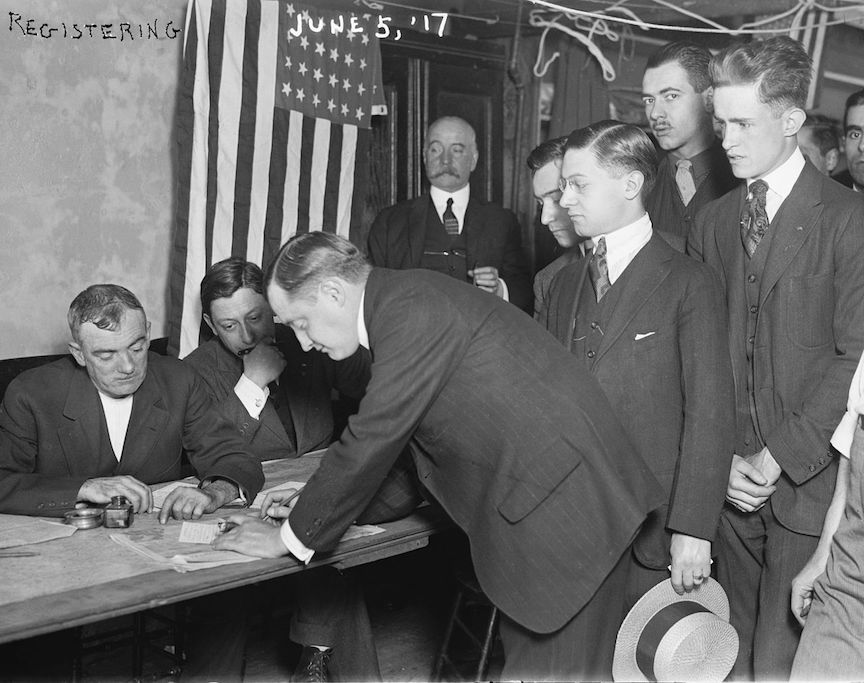

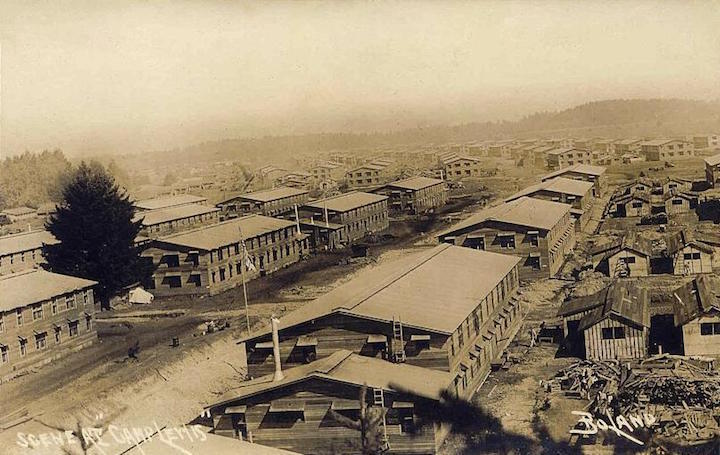

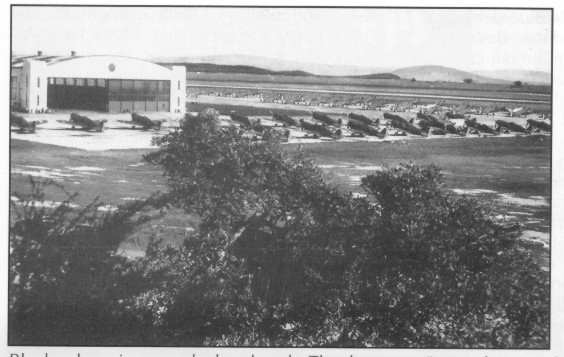

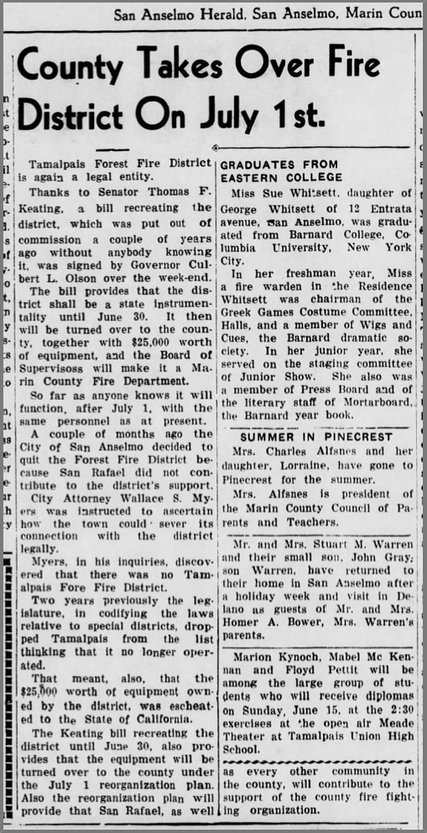

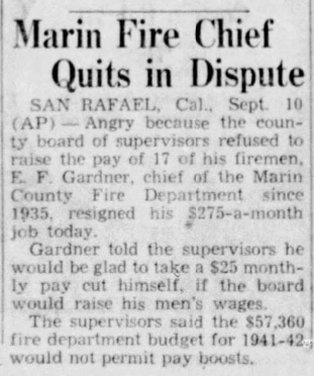

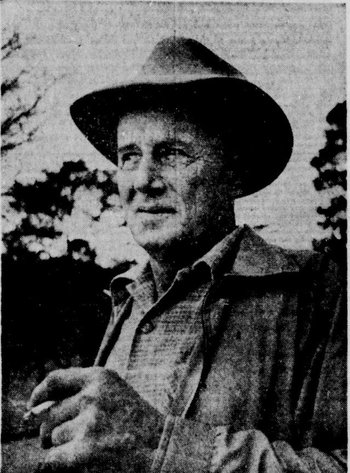

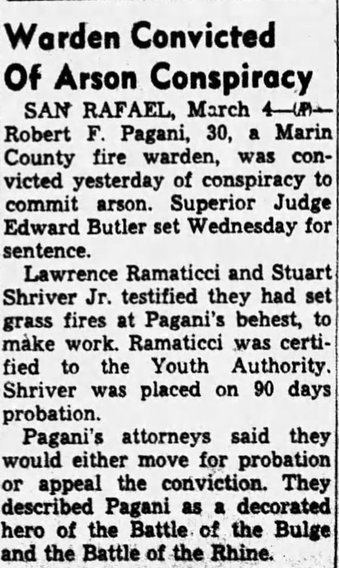

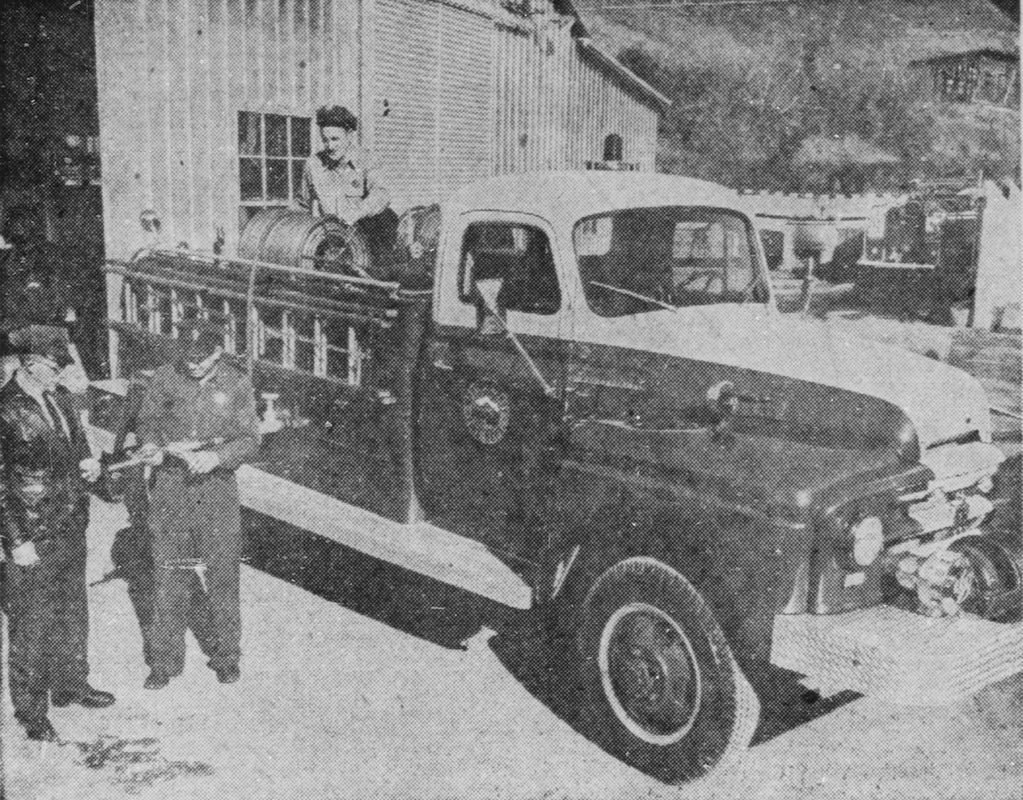

Looking back on the first nine years of the department, if ever there was an FD set up to take a fall, it was MCFD. This is a brief look at the very difficult first decade in their history, and in Part IV how Charlie Reilley would go on to improve the foundation of what became and remains one of the finest fire departments in California. The start of World War II within the first six months of the birth of the new department, in the opinion of the author, must have contributed to a rough beginning. Public and government attention and worries were focused on civil defense by necessity. In Marin, a possible invasion by the Japanese was part of the fears. The war of course required that most resources be put towards military needs. For example, no domestic cars were produced at all in the U.S. during World War II, most resources were rationed, such as tires and rubber, and getting new fire trucks and equipment was not allowed or difficult at best. Marin County already had multiple military installations and bases that would now grow. Sausalito soon had a major ship building operation through the Bechtel company, called Marinship. Another related factor impacting MCFD was the growth in Marin County’s population, both during and after World War II. This meant, among other things, more homes being built in unincorporated areas that included wildland interface. The County population increased by 63% from 1940-1950 , with the census in 1950 recording a total of roughly 87,000 people in the County. This growth in retrospect would suggest that MCFD evolve into a broader mission, what is called “all-risk” today, rather than primarily handling forest, brush, and grass fires. However, as is often the case with change in organizations including FD's, "old habits were hard to break," and the necessary political and community support and funding was not there. In fact, a public conflict over funding happened two months after the start of MCFD. As a stand-alone fire district, TFFD was a small and relatively simple organization. Getting things done was far easier in many ways. MCFD, on the other hand, operated within the much larger organization of County Government, and the former TFFD employees needed to adapt to this new complexity. In the larger organization, MCFD competed for limited public funds and personnel needs with other County departments, such as the Sheriff’s office and Public Works. Budgeting, policies, and procedures, including spending approvals, had to work within the much more complex County bureaucratic system. This alone would prove to be a difficult change for MCFD management, eventually resulting in an ugly audit by the end of the decade. In addition to World War II and it's many local impacts, the 1940's also included MCFD leading the fight to extinguish one of the largest known wildland fires in Marin County History in 1945, the Mill Fire, originating in Carson Canyon. Also in the first nine years, the department went through four fire chiefs, and in addition one acting Chief from the U.S. Forest Service. The first Fire Chief, E.F. Gardner, served for less than three months. He resigned after a decision by the Marin County Board of Supervisors (BOS) about salaries. Gardner, previously the TFFD Chief, believed the TFFD Board had approved pay raises in concept before dissolving the district earlier that year. He was working two jobs at the time 'to make ends meet', the other being general manager of the San Geronimo Water Company in Woodacre. Chief Gardner advised the BOS that given a pay increase he could serve full-time as the MCFD Chief, but without one he'd choose to only serve in the water company role. He also felt the other fire wardens all needed raises. The BOS declined to approve any increases, even with Gardner offering to give up some of his pay to give his men a raise. The BOS said the $56,360 annual budget could not afford raises or any other increases, and Gardner resigned. Assistant Fire Warden Lloyd de la Montana, Gardner's brother-in-law, became the next Chief in November of 1941. He had previously worked as a fire warden with TFFD for 11 years in Point Reyes, transferred into MCFD when it formed, and then promoted to Assistant Chief Fire Warden. He and his wife moved to Woodacre, and Americo Giambastiani took his place as the Warden in Point Reyes and Inverness. Giambastiani would later serve as the MCFD Assistant Fire Chief in the 1960's. Lloyd de la Montana lost his right arm when he was very young due to a hunting accident, and could not use a prosthetic due to the amputation being too far up his arm. He served for a little over five years before having to step down due to extended illness. After leaving MCFD in early 1947, he did some ranching for a few years, and then worked as a field deputy in the County Assessors Office. In 1951, he was promoted by the BOS to run the County Farm in Lucas Valley, serving until it closed in 1963. Look forward to a biography on Lloyd coming in the Marin Fire History project. Following Chief de la Montanya's resignation as County Fire Chief, Charles Smith of the U.S. Forest Service was appointed Acting Chief for two months before becoming unavailable. The next MCFD Fire Chief was Samuel Mazza, who started in July of 1947, and tragically died at a large grass fire on September 2, 1948 at the Rogers Ranch in Nicasio. Chief Mazza had been up all night at a bad house fire in Tomales, where a fatality occurred with an elderly resident. Mazza and his men had been working the Nicasio fire all day without any sleep. At one point Mazza left the Nicasio fire scene to help get food for the firefighters, and on the return trip became ill. His son was driving when the Chief asked him to pull over, saying he was in pain. He was having an heart attack, and when resuscitation efforts failed he passed away. He was a native of Marin, born in 1887 at Tocaloma, near what is now Samuel P. Taylor State Park . The next Marin County Fire Chief was Camillo Mello, a former Dairy Rancher who had served as Assistant Chief under Chief Mazza. Camillo viewed his role as managing the non-emergency operations of MCFD, while his Assistant Chief Jimmy Nettro headed up the the firefighting operations. A year into his tenure, Mello was confronted with a series of arson fires in the San Anselmo region. Investigations with San Anselmo Fire Chief Nello Marcucci revealed a sad story of a World War II battle veteran and current Marin County FD Fire Warden encouraging teenagers to set fires for work. The teenagers were part-time summer employees of MCFD, only called into action for fires. When 30-year old Warden Robert Pagani was convicted, the sentence was light, due in part, one assumes, to his Army service and the psychological impacts of the war. He was sentenced to eight months in County Jail, with four months having already been served, and had to pay some restitution to a fire victim, along with serving probation for several years. Meanwhile, one of the hardest systems for Chief Mello to adapt to was that of County budgeting, and properly following the policies and procedures. The County had a full-time Auditor, Leon de Lisle, who conducted an audit two years later that would prove to be the beginning of the end for Chief Mello's tenure. In addition, Mello had publicly opposed 1) a request from the BOS to consider outsourcing County fire protection to the California Department of Forestry (CDF), an option to save money, and 2) consideration of the formation of fire districts in unincorporated communities like Sleepy Hollow and Inverness. The headlines of December 19, 1950 in the Independent Journal read "County Fire Department Accused of 'Unorthodox' Financial Procedures." The charges in the Audit included work being done on employee vehicles in the FD shop; not keeping proper inventories; a reluctance to complete purchasing inside the County and spending more procuring materials and equipment outside; ordering equipment first and then making the required requisitions months later; failing to anticipate and budget items properly; and not following County policies and procedures in general. County Auditor de Lisle went on to accuse Mello of being a man "...who makes no pretense of being a fireman...", and stated that he was not qualified for the job. The Marin County Grand Jury then reviewed the report, and wrote their own harsh report. Mellos' 58-page response to the Grand Jury report disputed all charges, and attempted at length to explain that they were improper or inaccurate. The two-month old dispute was over on Feb 19, 1951, when the Board of Supervisors fired Mello, two weeks after Mello had fired Assistant Chief Nettro without BOS authorization. The BOS both reinstated Nettro and then made Warden Charlie Reilley the Acting Fire Chief. He would be made the full-time Chief a short time later. The BOS still considered the CDF option for several more years, although a formal proposal was never sought. Public controversy for MCFD continued throughout the 1950's, especially with what the primary mission should be - fighting vegetation fires or structure fires? This would not be a settled question for many years. In parallel during multiple controversies that had accrued from the first decade, Charlie would go on to quietly rebuild the Marin County fire department by the time of his retirement in 1962, at 65 years old. He distinguished himself both as a fire chief and a leader in Marin County, and MCFD went on to great success. He was once a hero in war, and also became a quiet hero in his last career. "All great and beautiful work has come of first gazing without shrinking into the darkness." - John Ruskin Sources: San Anselmo Herald, Marin Independent Journal, Petaluma Argus-Courier, Oakland Tribune, California Digital Newspaper Collection, Marin County Fire Department Historical Archives, Library of Congress. Coming soon in our final Part IV, Charlie's career as Fire Chief and his retirement.

|

|