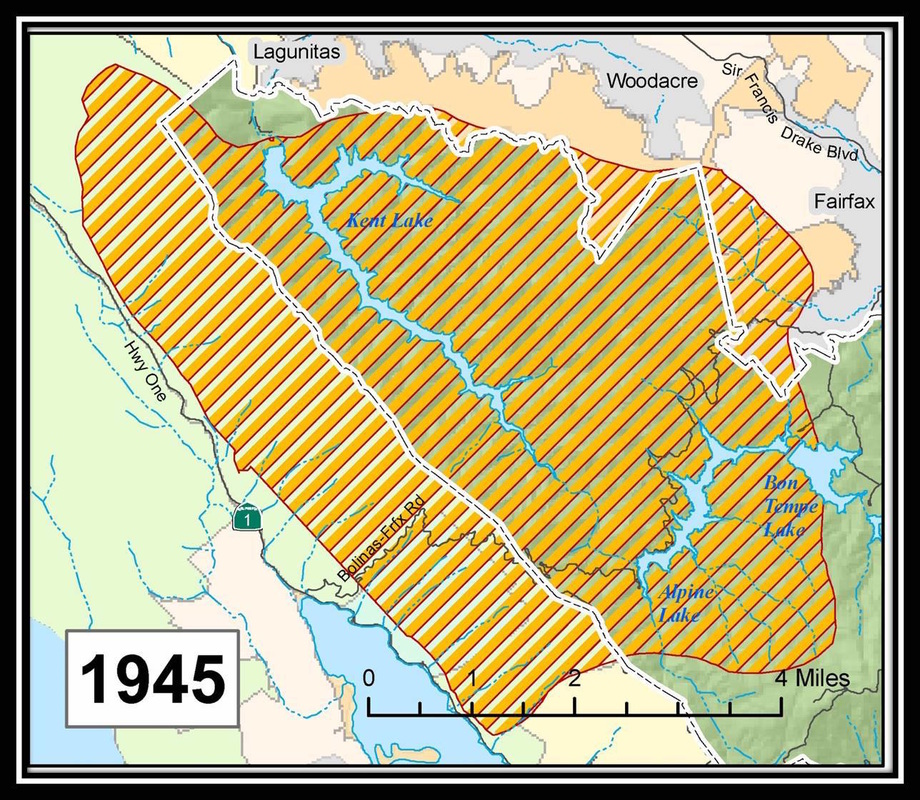

The Story of the huge 1945 Forest Fire in West Marin. This fire started above the Timber Mills near the West Marin community of Lagunitas, close to where the Kent Lake Dam was built in 1954.

Thanks to our contributors including: Dewey Livingston, Greg Jennings, Rich Testa, Pete Martin, and Laurie Thompson.

With thanks to West Marin Historian and Author Dewey Livingston, we are republishing his story of this fire that was written in January of 1986 for "The Fax." According to Dewey, "...this was a monthly --later weekly--local newspaper serving Fairfax, San Anselmo and the San Geronimo Valley, published from around 1985 to 1989 or so. That was where I got my start as a history writer, which turned into a professional career. I wrote a monthly history feature about the area for a few of those years.

They are all on file at the California Room." Thanks also to Laurie Thompson of the Anne T. Kent California Room Collection of the Marin County Free Library, for permission to use the two photos at the bottom of this page showing the fire from San Francisco, and an aerial photo of the aftermath.

The Fire That Made History in Marin

by Dewey S. Livingston

"It started as a common early fall brush fire on Thursday, September 27, 1945. The local daily reported the fire burning above the lumber mills in Lagunitas Canyon, that it was spreading up the hill, that another fire was reported near Bolinas Ridge. Soldiers were being recruited from Fort Barry to assist local firefighters. A simple paragraph at the bottom of page one.

Anyone watching the weather would have been concerned. A high-pressure area had spread across California during the week, drying further the already thirsty forests and brushlands. The hot wind from the east on that September day brought doom to the vast Mt. Tamalpais watershed, as the two fires joined to produce the largest blaze in Marin County history. Marinites had seen a few large blazes in their lifetimes. A huge fire on Bolinas Ridge in 1904 burned ranch houses and reached the Cascades above Fairfax before being contained.

The famed Summit House on the Bolinas Stage road was reportedly destroyed, as were numerous wooden bridges and valuable timber. A fire in the commercial district of Ross brought out nearby residents, “most of them members of the exclusive set,” to battle the blaze. The much publicized 1929 Mill Valley fire destroyed dozens of homes and closed the Mt. Tamalpais & Muir Woods Railroad for good. The little report of a remote fire probably didn't worry very many folks.

The residents at the county were busy with other things; the war had just ended and the War Chest Victory Drive was set to begin on the weekend, as two thousand volunteers mobilized for a door-to-door campaign to help the country get back on its feet. Rationing was on its way out, while "Jap” and Nazi war criminals were being hunted and the mop up in Europe and the Pacific was under way.

The fire wasn’t content to stay small. With the humidity at 12 percent and dry 45 mph westerly winds fanning the blaze in all directions it became front-page headlines by the next day. Within 24 hours the fire had consumed 2000 acres from Bolinas Lagoon to Camp Taylor. Now the flames headed east towards Alpine Lake, Woodacre and Fairfax.

County Fire Chief Lloyd De La Montanya led forces of firefighters, soldiers, convicts, volunteers, and high school boys to try to keep the fire away from the nearby population centers. Fire roads were scraped out by bulldozers and by hand. To the disappointment of the tired crews, the flames hopped here and there almost suspiciously. Other county crews were kept busy with blazes above Sausalito, San Rafael, and Chileno Valley.

By Saturday the fire reached within 1/4 mile of Stinson Beach, while on the other end of the conflagration Fairfax and Woodacre were threatened. Crossing the Alpine Dam road it roared up the north slopes of Mt. Tamalpais, wiping out the Marin Municipal Water District watershed. Wildlife was not spared as the dames and smoke surrounded families at horrified deer, raccoons, and certainly a mountain lion or two. In Fairfax and San Geronimo Valley 3000 residents were put on alert for evacuation.

From San Francisco the sight was awesome: a huge dark cloud to the north sending a rain of ashes to the city streets. The big papers in the city told of the destruction of Marin County as hundreds are evacuated, rumors that only added to the excitement of the distant views. Marinites looked with pride at the fact that no one was actually evacuated and that the huge battle was bravely and well fought. As the weather turned more favorable over the weekend new concerns arose. “Spasmodic" outbreaks of fire had plagued the crews since the beginning and arson was suspected.

Sheriff's observers were sent out on the lines to check for illegal backfiring or dangerous practices such as carrying shovelfuls of hot coals to light the trail in the dark. No arsonists were found although the suspicions lasted until after the fire was out. Meanwhile the local women went to work staffing the Canteen Corps units. By Saturday 12,000 sandwiches were reportedly made and sent to the fire lines. Disaster relief committees worked night and day preparing emergency quarters, providing transportation and organizing foods tor the firefighters.

The Ladies Auxiliary of the Fairfax Fire Department labored over vats of chili beans and coffee at all hours as the flames lit the ridges above them. After a full week of exhaustive effort and frustration the wind died and the fog drifted over the ridges from the coast. Aside From an occasional flare-up the blaze was conquered. The toll: up to 20,000 acres of forest, brush and pasture land in ashes, telephone poles throughout the bum destroyed, a great loss of wildlife, and one structure – “Camp Reposo”, the Little Carson cabin of the Lagunitas Rod and Gun Club - burned to the ground. One young firefighter was seriously injured, but the fact that the fire did not do more harm to dwellings and people was a source of wonder to those who witnessed the great fire.

The day the fire was officially out two Navy F4-U Corsair planes crashed head-on above the west peak of Mt. Tamalpais, causing a 200-acre fire to be dealt with by overtired crews. And, a few days later, a headline in the San Rafael Independent read, “3,850 lives lost in Fairfax Fire". The fire-happy editor was reporting a henhouse fire at the Smith Brothers' ranch near Whites Hill.

Visiting the scene of Marin's biggest fire three weeks later was John Thomas Howell, the distinguished author of Marin Flora, described the damage in an essay for the Sierra Club Yodeler –“The desolation was like that which one associates with the desert after prolonged drought, when even burro bushes look dead and cacti shrivel. The blackened, ashy front of Pine Mountain above Lagunitas Canyon resembled nothing so much as some sun-baked canyon side above Death Valley. Lagunitas Canyon was, in its way, a canyon of Death…”

Howell noted that already the plants were sprouting from the ashes, and as we can see today the whole area has regenerated to a full and healthy, if not overgrown state. But the scars of the great fire of 1945 can be seen everywhere on the trunks at the redwoods; big black marks to remind us of the extent of the destruction."

Footnote: The exact acreage burned as been reported anywhere from 15,000 to 40,000 acres total. We're not sure if these figures left out or included the other, smaller fires in Marin at that time. We will update this figure when we learn more.

They are all on file at the California Room." Thanks also to Laurie Thompson of the Anne T. Kent California Room Collection of the Marin County Free Library, for permission to use the two photos at the bottom of this page showing the fire from San Francisco, and an aerial photo of the aftermath.

The Fire That Made History in Marin

by Dewey S. Livingston

"It started as a common early fall brush fire on Thursday, September 27, 1945. The local daily reported the fire burning above the lumber mills in Lagunitas Canyon, that it was spreading up the hill, that another fire was reported near Bolinas Ridge. Soldiers were being recruited from Fort Barry to assist local firefighters. A simple paragraph at the bottom of page one.

Anyone watching the weather would have been concerned. A high-pressure area had spread across California during the week, drying further the already thirsty forests and brushlands. The hot wind from the east on that September day brought doom to the vast Mt. Tamalpais watershed, as the two fires joined to produce the largest blaze in Marin County history. Marinites had seen a few large blazes in their lifetimes. A huge fire on Bolinas Ridge in 1904 burned ranch houses and reached the Cascades above Fairfax before being contained.

The famed Summit House on the Bolinas Stage road was reportedly destroyed, as were numerous wooden bridges and valuable timber. A fire in the commercial district of Ross brought out nearby residents, “most of them members of the exclusive set,” to battle the blaze. The much publicized 1929 Mill Valley fire destroyed dozens of homes and closed the Mt. Tamalpais & Muir Woods Railroad for good. The little report of a remote fire probably didn't worry very many folks.

The residents at the county were busy with other things; the war had just ended and the War Chest Victory Drive was set to begin on the weekend, as two thousand volunteers mobilized for a door-to-door campaign to help the country get back on its feet. Rationing was on its way out, while "Jap” and Nazi war criminals were being hunted and the mop up in Europe and the Pacific was under way.

The fire wasn’t content to stay small. With the humidity at 12 percent and dry 45 mph westerly winds fanning the blaze in all directions it became front-page headlines by the next day. Within 24 hours the fire had consumed 2000 acres from Bolinas Lagoon to Camp Taylor. Now the flames headed east towards Alpine Lake, Woodacre and Fairfax.

County Fire Chief Lloyd De La Montanya led forces of firefighters, soldiers, convicts, volunteers, and high school boys to try to keep the fire away from the nearby population centers. Fire roads were scraped out by bulldozers and by hand. To the disappointment of the tired crews, the flames hopped here and there almost suspiciously. Other county crews were kept busy with blazes above Sausalito, San Rafael, and Chileno Valley.

By Saturday the fire reached within 1/4 mile of Stinson Beach, while on the other end of the conflagration Fairfax and Woodacre were threatened. Crossing the Alpine Dam road it roared up the north slopes of Mt. Tamalpais, wiping out the Marin Municipal Water District watershed. Wildlife was not spared as the dames and smoke surrounded families at horrified deer, raccoons, and certainly a mountain lion or two. In Fairfax and San Geronimo Valley 3000 residents were put on alert for evacuation.

From San Francisco the sight was awesome: a huge dark cloud to the north sending a rain of ashes to the city streets. The big papers in the city told of the destruction of Marin County as hundreds are evacuated, rumors that only added to the excitement of the distant views. Marinites looked with pride at the fact that no one was actually evacuated and that the huge battle was bravely and well fought. As the weather turned more favorable over the weekend new concerns arose. “Spasmodic" outbreaks of fire had plagued the crews since the beginning and arson was suspected.

Sheriff's observers were sent out on the lines to check for illegal backfiring or dangerous practices such as carrying shovelfuls of hot coals to light the trail in the dark. No arsonists were found although the suspicions lasted until after the fire was out. Meanwhile the local women went to work staffing the Canteen Corps units. By Saturday 12,000 sandwiches were reportedly made and sent to the fire lines. Disaster relief committees worked night and day preparing emergency quarters, providing transportation and organizing foods tor the firefighters.

The Ladies Auxiliary of the Fairfax Fire Department labored over vats of chili beans and coffee at all hours as the flames lit the ridges above them. After a full week of exhaustive effort and frustration the wind died and the fog drifted over the ridges from the coast. Aside From an occasional flare-up the blaze was conquered. The toll: up to 20,000 acres of forest, brush and pasture land in ashes, telephone poles throughout the bum destroyed, a great loss of wildlife, and one structure – “Camp Reposo”, the Little Carson cabin of the Lagunitas Rod and Gun Club - burned to the ground. One young firefighter was seriously injured, but the fact that the fire did not do more harm to dwellings and people was a source of wonder to those who witnessed the great fire.

The day the fire was officially out two Navy F4-U Corsair planes crashed head-on above the west peak of Mt. Tamalpais, causing a 200-acre fire to be dealt with by overtired crews. And, a few days later, a headline in the San Rafael Independent read, “3,850 lives lost in Fairfax Fire". The fire-happy editor was reporting a henhouse fire at the Smith Brothers' ranch near Whites Hill.

Visiting the scene of Marin's biggest fire three weeks later was John Thomas Howell, the distinguished author of Marin Flora, described the damage in an essay for the Sierra Club Yodeler –“The desolation was like that which one associates with the desert after prolonged drought, when even burro bushes look dead and cacti shrivel. The blackened, ashy front of Pine Mountain above Lagunitas Canyon resembled nothing so much as some sun-baked canyon side above Death Valley. Lagunitas Canyon was, in its way, a canyon of Death…”

Howell noted that already the plants were sprouting from the ashes, and as we can see today the whole area has regenerated to a full and healthy, if not overgrown state. But the scars of the great fire of 1945 can be seen everywhere on the trunks at the redwoods; big black marks to remind us of the extent of the destruction."

Footnote: The exact acreage burned as been reported anywhere from 15,000 to 40,000 acres total. We're not sure if these figures left out or included the other, smaller fires in Marin at that time. We will update this figure when we learn more.